INTRODUCTION

In Ecuador, the "Electric Peak and Plate" emerged as a temporary measure implemented through Ministerial Agreement No. MDT-2024-200, issued on October 22, 2024. This regulation allows for the modification of both regular and special working hours in response to the energy crisis affecting the country. The measure, aimed at private sector employers and employees, seeks to mitigate the effects of prolonged power outages. Research on this topic gains relevance not only due to its immediate implications for the productive sector but also because of its impact on regulatory compliance and business adaptation to critical situations. Based on data collected through surveys and interviews, this study assesses the consequences and benefits of the "Electric Peak and Plate" within the Ecuadorian labor landscape, proposing solutions to optimize its implementation.

Since 2023, Ecuador has faced significant challenges in its energy sector, primarily due to a decline in hydroelectric power generation resulting from the El Niño phenomenon and a prolonged drought (World Bank, 2024, p. 12). The International Energy Agency (IEA) reports that hydroelectric sources generate 85% of Ecuador's electricity, which increases the national power system's vulnerability to severe climatic events (IEA, 2024, p. 34). In this context, the adoption of strategies such as the "Electric Peak and Plate" has emerged as a recent alternative to address the consequences of the energy crisis. However, it also presents challenges for both companies and employees.

The study by Soria et al. (2024, p. 13) highlights that the reduction in working hours and the flexibilization of shifts not only impact productivity, but also present challenges for companies in adapting to new operational models. This may entail restructuring work schedules and investing in alternative energy solutions. Therefore, the implementation of energy strategies such as the "Electric Peak and Plate" has an uneven impact across the business sector. According to the ECLAC study (2024, p. 45), small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are the most affected due to their limited economic and technological resources. These entities face difficulties in acquiring autonomous energy generation systems, leading to an 18% increase in operating costs during the crisis (ECLAC, 2024, p. 47). Nonetheless, despite these challenges, the strategy has also encouraged innovation in energy management, stimulating investments in solar panels and other green technologies, as noted by González and Paredes (2024, p. 112).

General Objective

To analyze the "Electric Peak and Plate" implemented in Ecuador during 2024 about labor productivity and the economic performance of companies, identifying the challenges and opportunities generated by this measure in response to the energy crisis.

Specific Objectives

- To identify the effects of the "Electric Peak and Plate" on working hours and company productivity.

- To examine the economic and operational challenges faced by small and medium-sized enterprises due to this measure.

- To analyze the strategies implemented by companies to adapt and improve their energy efficiency in response to the crisis.

Justification of the Research

The relevance of this research lies in the need to understand the multidimensional impacts of the "Electric Peak and Plate" within the context of an energy crisis. Although a temporary measure, it has consequences that extend beyond business productivity, also affecting compliance with labor regulations and the functioning of business operations.

Evaluating both the benefits and challenges of this regulation is crucial for identifying areas for improvement and proposing strategies that strike a balance between operational efficiency and labor rights protection. This study also contributes to the discussion on how to manage similar crises in the future.

The implementation aims to adjust work schedules based on energy availability. Understanding how this measure affects workers and businesses is crucial to assess its effectiveness and sustainability. This research analyzes the benefits and challenges faced by the labor sector, as well as the implications for the future of work in Ecuador (López, 2024). Additionally, it is essential to evaluate whether these measures are being applied fairly and equitably to labor rights.

The analysis of the benefits and challenges of implementing the "Electric Peak and Plate" should include a comprehensive perspective that considers both the direct impact on company operations and the indirect impact on employees' quality of life.

Dueñas (2024) notes that a company's ability to maintain productivity under time and energy constraints is crucial in evaluating the effectiveness of such policies. Strategies employed by companies to mitigate the effects of the energy crisis, such as the adoption of renewable energy sources or scheduling optimization, can lead to more sustainable operational practices that benefit both employers and employees.

Moreover, as Miño (2024) highlights, this policy must be implemented with respect for workers' rights. Although the energy crisis calls for extraordinary measures, the protection of workers' rights such as working hours and wages must remain a top priority. The fair application of labor laws is crucial to avoid potential social conflicts caused by poor energy policies. Furthermore, this research is essential for developing long-term solutions to future energy crises.

As Prado (2024) states, the public and private sectors must collaborate to find sustainable solutions, not only to address the immediate crisis but also to establish solid foundations for the future. Inter-institutional coordination and investment in energy infrastructure will enhance the efficiency and equity of mitigating future energy crises.

In conclusion, the need to comprehensively assess the impact of the "Electric Peak and Plate" in the context of the energy crisis justifies this study, not only in terms of productivity but also in terms of employee respect. The successful implementation of this measure requires a balanced approach that promotes both energy efficiency and social justice, both of which are essential to responding more effectively and sustainably to future energy crises.

Context of the Energy Crisis in Ecuador

Ecuador has been facing an energy crisis since 2023, primarily due to severe droughts that have impacted hydroelectric generation, which accounts for approximately 80% of the country's electricity production (Primicias, 2024). The situation has worsened due to rising electricity demand, maintenance issues in hydroelectric plants, and limited reliance on alternative energy sources.

According to Soria et al. (2024), Ecuador's energy transition has affected labor productivity, particularly in sectors that rely heavily on electricity supply. The "Electric Peak and Plate" is part of the policies implemented to reduce energy demand during peak hours and to mitigate prolonged blackouts that impact industries. While these measures are necessary to address the crisis, they also affect business efficiency and worker productivity. This context has led to extended blackouts that negatively impact the economy, increase companies’ operating costs, and reduce the quality of life for citizens. Under these circumstances, the "Electric Peak and Plate" emerges as a palliative measure aimed at ensuring the continuity of labor activities amid scarcity.

The implementation of the "Electric Peak and Plate" presents various challenges. On the one hand, it seeks to mitigate the impact of blackouts on the productive sector. On the other, it raises questions about companies’ capacity to adapt to the regulation and ensure compliance.

The effectiveness of the supervisory mechanisms established by authorities is also under scrutiny. Furthermore, the lack of a stable electricity supply forces companies to incur extraordinary costs to reduce operational impact, which affects their competitiveness and sustainability in the market (Luzuriaga & Castro, 2024). This situation creates an environment of economic uncertainty in which companies must make strategic decisions to maintain productivity while facing possible penalties for non-compliance with energy regulations.

Legal Framework of the “Electric Peak and Plate”

Regulatory Basis: Ministerial Agreement No. MDT-2024-200 establishes the foundation for implementing the "Electric Peak and Plate" within the labor sector. This regulation emerged in the context of an energy emergency, allowing employers to adjust work schedules in response to energy availability while complying with the provisions of the Labor Code. Specifically, Article 42 requires employers to ensure decent working conditions, even during times of crisis (Lexis, 2024).

This regulation aims to strike a balance between the needs of companies and the rights of workers by establishing clear limits to prevent abuse. The agreement includes provisions for compensating overtime and rest days by the inalienable rights established in Article 4 of the Labor Code. This means that any adjustments to work schedules must be fairly agreed upon and cannot result in the loss of employee benefits. Additionally, employers are required to communicate such changes in advance and appropriately to avoid labor conflicts (Primicias, 2024).

This regulation is essential in the current context as it provides a legal framework to address the energy crisis without interrupting business productivity. At the same time, it emphasizes the need for supervision by the Ministry of Labor to ensure proper implementation. This balance between business flexibility and labor protection is a key aspect of the agreement.

According to Meythaler and Zambrano (2024), the "Electric Peak and Plate" has prompted many companies to invest in technologies to optimize energy use. This emerging trend could encourage long-term sustainable practices. Conversely, López (2024) points out that small and medium-sized enterprises face greater challenges due to limited adaptive capacity, highlighting the need for differentiated policies for vulnerable sectors.

Impact of the “Electric Peak and Plate” on Labor Productivity

According to Almeida (2024), the "Electric Peak and Plate" system implemented by the government has directly affected the distribution of workload across Ecuadorian sectors, particularly those whose production processes rely on continuous electricity. An official report from the Ministry of Energy and Mines highlights the government's efforts to ensure operational continuity in key sectors while acknowledging that these measures have impacted productivity during peak hours, especially among small and medium-sized enterprises.

During the first three weeks of blackouts, experts estimated losses at USD 2 billion. This economic impact increased significantly over time, and after two months of power interruptions, the Quito Chamber of Commerce estimated that the industrial sector suffered losses of USD 4 billion, while the commercial sector experienced a decline of USD 3.5 billion. These figures reflect the severe damage to productivity and competitiveness, as many companies halted operations, reduced working hours, and, in many cases, temporarily shut down their operations.

Calderón de Burgos (2024) also argues that capacity limitations affect not only company productivity but also employee morale, as workers must rearrange their schedules to meet demands under energy restrictions. In a column published in El Universo, she noted that while these policies may be necessary, they create social and economic tensions due to the lack of apparent alternatives for the most vulnerable businesses.

In contrast, Rosero (2024) highlights that initiatives such as the “Electric Peak and Plate” have a particularly severe impact in rural areas, where access to technologies that ease energy restrictions is limited. Data published in Coyuntura Económica magazine indicated that labor productivity in rural areas of the country fell by 15%. Neither the Ecuadorian Business Committee nor the Quito Chamber of Commerce provided exact figures on direct or indirect job losses related to the recent blackouts. However, both organizations estimate that each hour without electricity results in approximately USD 12 million in losses, totaling USD 96 million for an eight-hour workday.

Marcela Arellano, president of the Ecuadorian Confederation of Free Trade Union Organizations (Ceols), noted that although there is no precise data on the impact on small and medium-sized enterprises—which account for 93% of employment in the country—the consequences after one month of blackouts are already evident, affecting both the quantity and quality of jobs.

Labor Rights and the Energy Crisis

Labor legislation in Ecuador ensures respect for fundamental rights, including fair remuneration, reasonable working hours, and decent working conditions (Lexis, 2024). In this regard, the Labor Code enshrines the inalienability of workers' rights (Art. 4), ensuring that any agreement contrary to these provisions is considered null and void.

Article 42 of the Labor Code outlines the obligations of employers, including the timely payment of wages and compliance with applicable legal provisions. This implies that any modification to working hours must respect the rights established by current regulations, including compensation for overtime and adherence to rest days.

Ministerial Agreement No. MDT-2024-200 establishes a temporary framework for flexibilizing working hours while ensuring respect for fundamental labor rights as stipulated in Article 4 of the Ecuadorian Labor Code. This includes compensation for extra hours and compliance with mandatory rest periods (Lexis, 2024, p. 89). However, reports by Primicias (2024, p. 7) suggest that the Ministry of Labor’s limited supervisory capacity has led to cases of non-compliance, leaving some companies and workers vulnerable to precarious working conditions.

Currently, elements such as contracts, insurance policies, and force majeure clauses are being reviewed and modified by many companies to anticipate and prepare for power outages. These strategies reflect a growing trend toward legal risk prevention and corporate security, aiming to prevent future disputes and minimize the economic impact of unforeseen events. Moreover, some companies have acquired specialized insurance to cover energy crises, allowing them to offset lost income and other related expenses.

However, the insurance market does not always cover prolonged and recurring blackouts, forcing companies to adopt other mitigation strategies. In this context, legal experts are scrutinizing force majeure clauses to determine whether such events fall under these provisions. At the same time, specific sectors are considering legal action to seek compensation for incurred damages, arguing that the State is responsible for ensuring basic electricity supply. Power outages are not entirely unforeseeable, potentially opening a debate about the State's responsibility in maintaining the energy infrastructure necessary for economic development and its relationship with the private sector.

Impact on the Business and Legislative Environment

The measure introduces significant changes to business operations and necessitates strict oversight by the authorities. Companies must adjust their strategies to comply with the regulation without compromising productivity, while the authorities face the challenge of ensuring fair and effective implementation. Moreover, Article 7 of the Labor Code states that any ambiguity in the interpretation of labor provisions must be resolved in favor of the worker, providing greater protection against potential abuses.

It is particularly difficult for companies, especially small and medium-sized enterprises to adapt to electricity consumption and pricing limits (such as maximum usage and grid tariffs). Many businesses have implemented flexible schedules and autonomous energy generation systems, which have increased their operating costs. However, reports such as Cueva and Torres (2024) highlight that these crises may encourage sustainable investments, such as the adoption of solar panels.

The Central Bank of Ecuador (2024) forecasts that the introduction of incentives for renewable energy could increase business productivity by 3% in the medium term. However, unlike countries like Colombia, Ecuador lacks a stable system of tax incentives for these technologies (González & Paredes, 2024).

In the current situation, businesses face significant challenges due to the energy crisis and require innovative and collaborative strategies to remain operational and ensure sustainable development. Ricardo Dueñas (2024) notes that companies must take creative actions, such as using automatic generators and planning phased schedules.

These measures not only reduce the impact of power outages but also optimize resources and maintain productivity. He cited successful cases in which such initiatives reduced operating costs by 20%, while the use of sustainable technologies—such as solar panels and energy storage systems—increased company resilience to future crises. He argues that innovation should become a strategic focus in the current business environment.

Along these lines, Nancy Mignot (2024) reinforces this perspective, emphasizing the importance of ensuring compliance during the implementation of such measures. She stressed that companies must not jeopardize employees' labor rights, even during an energy crisis. The report emphasizes that transparent negotiations regarding schedule adjustments and adherence to overtime regulations are crucial to avoid legal sanctions and maintain employee trust. She warned that non-compliance not only entails legal risks but can also negatively affect a company's reputation. For this reason, she emphasized that balancing business continuity and respect for employee rights during the energy crisis is key to organizational success (Miño, 2024).

Prado (2024), meanwhile, emphasized the need for a collaborative approach between the public and private sectors to address this issue sustainably. He noted that the Ecuadorian government offers tax incentives to companies that invest in sustainable energy solutions, including renewable energy and energy-efficient equipment. The policy aims not only to ease immediate pressures from the crisis but also to promote a transition to cleaner and more diversified energy models. He also mentioned that ongoing dialogue between the State, business associations, and labor unions is essential to ensure that adopted solutions benefit both the manufacturing sector and workers, promoting fair and sustainable development (Prado, 2024).

Together, these perspectives provide a comprehensive approach for companies to address the energy crisis. Dueñas emphasized the importance of operational innovation, Miño highlighted the need for legal compliance, and Prado advocated for intersectoral collaboration as a sustainable solution. This holistic approach emphasizes that an effective response to the energy crisis necessitates strategic action in multiple areas to ensure corporate sustainability, protect labor rights, and facilitate a transition to more resilient and sustainable energy systems. Nevertheless, despite the implementation of these measures to face blackouts—which at times lasted up to 14 hours a day—companies were still financially affected, and some had no choice but to lay off staff, as the following data from La Hora (2024) shows:

- 59% reported an increase in operating costs.

- 22% faced delays in delivering products and services.

- 21% experienced a significant reduction in production and operations.

- 5% had to resort to layoffs or staff reduction.

Business Implications

Operational Adjustments: The implementation of the "Electric Peak and Plate" has forced companies to reconsider their operational strategies. Many have rescheduled shifts and adopted technologies that optimize the use of available energy resources. These adaptations, although necessary, have generated additional costs related to planning and staff training to manage new systems (López, 2024). However, these strategies also represent an opportunity to improve long-term operational efficiency.

One of the primary challenges is the unpredictability of power outages, which complicates business activity planning. Companies must design flexible schedules that meet deadlines, which often requires hiring additional staff or intensive use of electric generators (Primicias, 2024). Although effective, these measures increase operating costs and affect business profitability, particularly in sectors such as commerce and manufacturing. On the other hand, the "

Electric Peak and Plate" has also encouraged innovation in processes and cross-sector collaboration. Many companies have formed alliances with technology providers to implement energy monitoring systems that optimize electricity use. These practices can serve as models for other companies, thereby strengthening the resilience of Ecuador's business sector (Forbes, 2024).

Economic Impact: The measure has had mixed economic effects. On the one hand, it allows companies to maintain operations without resorting to temporary closures, preserving jobs and avoiding significant losses. On the other hand, it creates additional expenses in terms of logistics, backup technologies, and staff training (Meythaler & Zambrano, 2024). These costs are especially burdensome for small and medium-sized enterprises, which have limited resources to meet such demands.

The implementation of the agreement has also created inequalities among economic sectors. While some industries, such as technology and financial services, can quickly adapt, others like agriculture and manufacturing—face greater challenges due to their reliance on energy-intensive processes (Primicias, 2024). This highlights the need for complementary policies that provide specific support to the most vulnerable sectors.

Nevertheless, in the long term, these measures could drive a transition toward more sustainable business models. Companies that effectively adapt to the "Electric Peak and Plate" will not only reduce their operating costs but also improve their competitiveness by implementing more efficient and environmentally responsible practices (López, 2024).

Compliance and Oversight

Role of the Ministry of Labor: The Ministry of Labor plays a crucial role in overseeing the correct implementation of the "Electric Peak and Plate." According to Article 539 of the Labor Code, the Ministry is responsible for conducting regular inspections to ensure that employers comply with legal provisions and respect workers' rights (Lexis, 2024).

These inspections include reviewing work schedules and following up on employee complaints. Despite these efforts, the Ministry's oversight capacity faces limitations due to a lack of personnel and resources. This has led to non-compliance cases affecting both workers and business competitiveness. The creation of anonymous reporting systems and the digitization of oversight processes could significantly improve the effectiveness of these inspections (Primicias, 2024).

The Department of Labor conducts regular inspections to ensure compliance with electricity-related adjustments and exemptions, as required by Section 539 of the Labor Code. However, according to the National Office (2024), there is a 30% shortage of labor inspectors, which limits the effectiveness of these inspections. Proposals such as digitizing processes and creating anonymous reporting channels aim to increase control and transparency in the enforcement of the regulation.

Corrective Actions: In cases of non-compliance, the Ministry has the authority to impose economic and legal sanctions on employers who violate the regulation. These sanctions, established under Article 628 of the Labor Code, aim to deter practices that infringe on workers' rights, such as unpaid overtime or failure to notify schedule changes (Meythaler & Zambrano, 2024). However, authorities should accompany these corrective actions with awareness campaigns to prevent future violations. Additionally, the Ministry of Labor is developing digital platforms to facilitate the submission of complaints and access to regulatory information. These initiatives not only strengthen enforcement but also empower workers by providing them with practical tools to defend their rights (Forbes, 2024).

METHODS

The researchers used a quantitative approach with a non-experimental, descriptive design. This approach enables the analysis of available data on the impact of the "Electric Peak and Plate" on labor productivity and economic performance in Ecuador without direct intervention in the context. According to Hernández-Sampieri et al. (2022), this type of design is ideal for examining phenomena as they occur in their natural reality and for conducting statistical analyses based on secondary data.

The cross-sectional descriptive design allowed for the collection and analysis of information from previously published sources at a single point in time, corresponding to the year 2024, to identify patterns and trends related to the effects of the implemented measure.

Data Collection Methods

- Document Review: The researchers thoroughly analyzed regulatory documents, official reports, academic articles, and news articles related to the "Electric Peak and Plate." Key sources included:

- Ministerial Agreement No. MDT-2024-200, which governs the implementation of the "Electric Peak and Plate."

- Reports from institutions such as the Central Bank of Ecuador and the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC).

- Surveys directed at companies from various economic sectors in Ecuador. The questions focused on indicators of productivity, operating costs, and adjustments made as a result of the "Electric Peak and Plate." Martínez Torrico and Aliaga Lordemann (2016) support this approach and highlight the value of structured tools in economic studies.

- To evaluate economic and productivity trends before and after the implementation of the measure, data and statistics were gathered from organizations such as the Central Bank of Ecuador and the National Institute of Statistics and Censuses (INEC).

- Statistical Data Analysis: Statistics from reliable sources were collected and analyzed to evaluate the effects of the "Electric Peak and Plate" on labor productivity and economic performance. The statistical sources considered included:

- Economic impact reports published by Russell Bedford Ecuador and Ecuador Chequea.

- Data on economic losses and labor impacts generated by digital media.

- Official indicators from the Central Bank of Ecuador and specialized reports on the energy crisis.

RESULTS

The implementation of the "Electric Peak and Plate" in Ecuador in 2024 showed a significant impact on labor productivity and the economic performance of companies. As a positive outcome, it partially mitigated the consequences of prolonged power outages, allowing critical sectors to continue operating. Companies adopted measures such as reorganizing work schedules, implementing flexible shifts, and using electric generators. These strategies helped to cushion the adverse effects of the energy crisis and ensured the continuity of essential activities.

The analysis below presents the most relevant findings:

General Impact on Productivity and the Economy

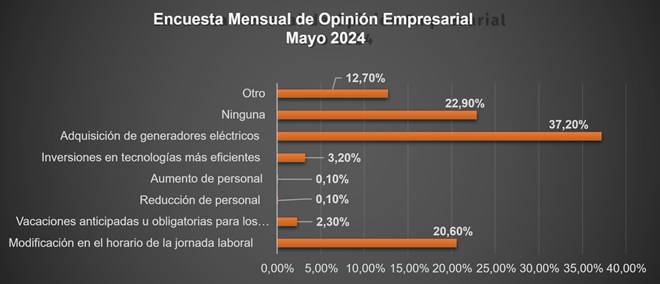

1. Measures adopted by companies during the energy emergency: Businesses implemented various strategies to mitigate the effects of prolonged power outages, including:

- Reorganization of work schedules

- Use of electric generators

- Adaptation to flexible shifts

These actions were particularly relevant in critical sectors such as industry and services, where maintaining operational continuity was essential.

Figure 1

Source: Central Bank of Ecuador.

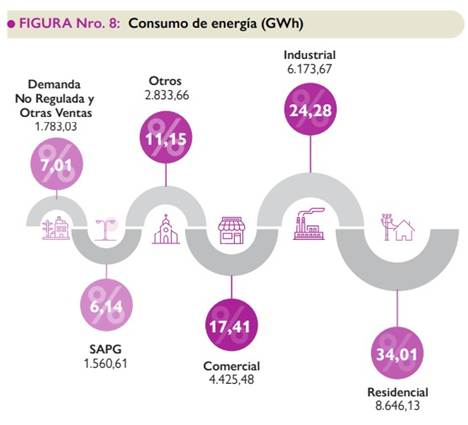

2. Distribution of energy consumption by sector: The analysis reveals that the most affected productive sectors were those with high energy dependence, including manufacturing, commerce, and the service sector. Energy consumption by industry revealed disparities in the ability to respond to the crisis, highlighting the need for differentiated policies.

Figure 2

Source: Agency for the Regulation and Control of Energy and Non-Renewable Natural Resources.

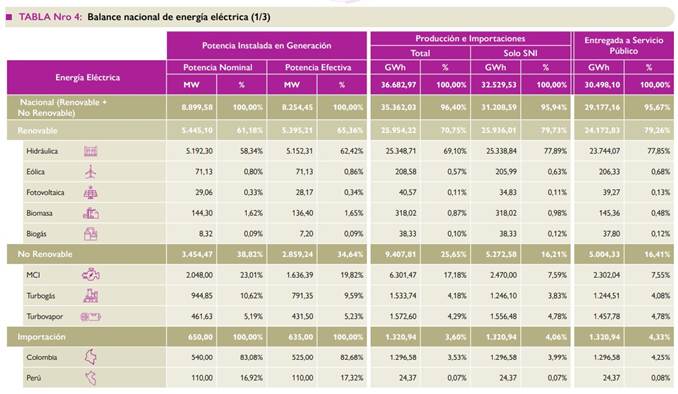

Transition Toward Sustainable Models

3. National Electric Energy Balance: The energy crisis and the measures under the “Electric Peak and Plate” highlighted the limitations of the national electrical system, whose dependence on hydroelectric sources exposes the country to climate-related vulnerabilities. According to the national energy balance, there was a significant decline in electricity generation compared to previous years.

Figure 3

Source: Agency for the Regulation and Control of Energy and Non-Renewable Natural Resources.

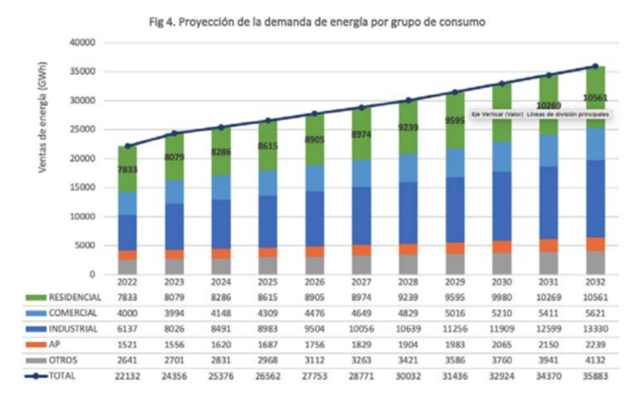

4. Energy Demand Projection: Despite the crisis, medium-term projections indicate an increase in energy demand due to population growth and economic recovery. This highlights the importance of diversifying energy sources to ensure long-term sustainability.

Figure 4

Source: Master Electrification Plan (PME)

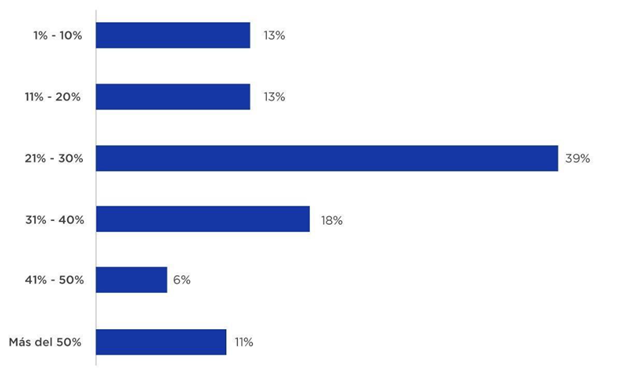

Economic Challenges

5. Estimates of Economic Losses: Energy interruptions caused significant economic losses for Ecuadorian companies. These losses are estimated to have reached considerable levels, particularly among SMEs, which lack sufficient resources to implement alternative energy solutions.

Figure 5

Source: Quito Chamber of Commerce.

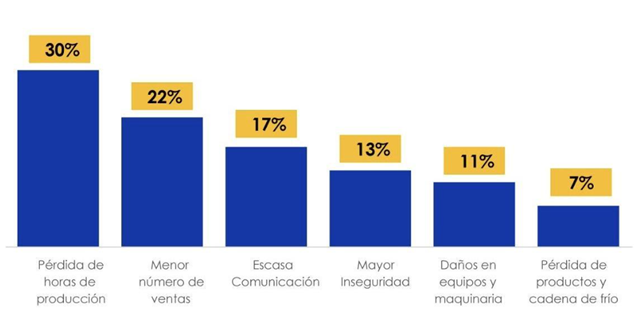

6. Specific Impacts on Businesses: The main reported effects include:

· Reduction in labor productivity.

· Increase in operating costs resulting from the use of generators and other mitigation measures.

· Difficulties in meeting commercial commitments due to the unpredictability of power outages.

Figure 6

Source: Quito Chamber of Commerce.

The energy crisis has also presented an opportunity for transitioning to a more sustainable model.

According to Cueva and Torres (2024, p. 56), investments in renewable technologies such as solar panels and wind turbines have increased by 12% since the implementation of the “Electric Peak and Plate.” However, these initiatives must be accompanied by fiscal and financial incentives, as is the case in neighboring countries like Colombia, where the adoption of renewable energy is more competitive thanks to stronger public policies (González & Paredes, 2024, p. 89).

According to the Central Bank of Ecuador (2024, p. 23), introducing incentives for sustainable energy could increase business productivity by 3% in the medium term. Nonetheless, the additional costs resulting from these operational adaptations mainly affected small and medium-sized enterprises, which faced difficulties in covering expenses such as purchasing energy equipment and staff training. Moreover, the unpredictability of power outages complicates operational planning, negatively impacting labor productivity. From a legal standpoint, the regulation ensured the protection of fundamental labor rights, such as compensation for overtime and respect for rest days. However, the Ministry of Labor's limited oversight capacity left some companies and workers vulnerable.

DISCUSSION

The implementation of the "Electric Peak and Plate" in Ecuador in 2024 had a direct impact on business economics, resulting in a significant increase in operating costs, particularly for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). These businesses, which represent a key pillar of the national economy, faced cost increases of up to 18% due to the acquisition of electric generators and the reorganization of work schedules (ECLAC, 2024). Although these strategies partially mitigated productivity losses, the unpredictability of energy cuts exacerbated the situation, hindering operational planning and negatively impacting business competitiveness, particularly in energy-intensive sectors such as manufacturing and commerce.

On the other hand, the results underscore the importance of transitioning to more sustainable energy models as a medium- to long-term economic response. The 12% growth in investments in renewable energies, such as solar panels, demonstrates the business sector's interest in reducing dependence on the hydroelectric system, which is highly vulnerable to climatic phenomena like El Niño (Cueva & Torres, 2024). However, these initiatives require tax incentives to be accessible, especially for SMEs. Countries like Colombia have demonstrated that robust public policies in this area can enhance business competitiveness and facilitate an efficient energy transition (González & Paredes, 2024). In Ecuador, the Central Bank (2024) estimates that appropriate incentives could increase business productivity by 3%, highlighting the need for strategies that enhance both economic performance and energy sustainability.

CONCLUSIONS

Although the “Electric Peak and Plate” was a temporary measure designed to confront an unprecedented energy crisis, it proved to be an effective mechanism for reducing electricity consumption during critical hours. However, the results also reveal that Ecuadorian businesses are not fully prepared to handle energy crises of this magnitude. The measure exposed structural weaknesses in the adaptability of companies, particularly those that heavily depend on a continuous energy supply to maintain productivity.

From a labor perspective, balancing the protection of workers' rights with business needs was one of the most significant challenges to address. While the current legal framework provided minimum safeguards for employees, the lack of adequate supervision led to inequalities in the application of the regulation. Furthermore, its implementation underscored the need to move toward a more sustainable energy model and to strengthen business infrastructure to face future crises.

Finally, although the “Electric Peak and Plate” allowed some sectors to maintain essential operations, it exposed the structural weaknesses of Ecuador’s economic system in the face of energy crises. The reported financial losses, combined with the limited regulatory oversight by the Ministry of Labor, highlight disparities in companies' ability to adapt based on their size and location. This underscores the urgency of designing differentiated policies that prioritize the most vulnerable sectors and strengthen the country's energy infrastructure. Furthermore, as the existing literature notes (González & Sánchez, 2024), ensuring a balance between labor productivity and economic performance is essential for temporary measures like this to contribute to a sustainable economic recovery.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Strengthen labor supervision and oversight: The Ministry of Labor should enhance its capacity to ensure compliance with regulations. This includes hiring more labor inspectors, digitizing oversight processes, and establishing anonymous reporting mechanisms for workers who are affected.

Experts recommend designing and implementing tax incentives and subsidies to encourage the adoption of sustainable technologies, such as solar panels and clean energy generators, particularly in small and medium-sized enterprises.

Design sector-specific contingency plans: Industries, in collaboration with the government, should establish tailored strategies to address future energy crises. These plans must include clear communication protocols and adaptive operational strategies to minimize disruptions and ensure continuity.

Foster awareness and training: Experts recommend implementing educational programs for companies and their workers to promote efficient energy use and emphasize the importance of adopting long-term, sustainable practices.

Implement differentiated policies: Due to sectoral disparities in adaptive capacity, specific guidelines should be developed to support the most vulnerable sectors, such as agriculture and manufacturing, which face greater challenges in the context of energy crises.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

Almeida, D. “Informe sobre el impacto del Pico y Placa Eléctrico en Ecuador.” Ministerio de Energía y Minas., https://www.envisionesl.com/es/blog/streamlining-port-operations-the-power-of-envisions-container-terminal-operating-systems-ctos.

Banco Central del Ecuador. (2024). Proyecciones económicas y sostenibilidad.

Banco Central. (2024). Impacto de las políticas energéticas en la productividad empresarial en Ecuador. Banco Central del Ecuador. https://www.bce.ec.

Calderón de Burgos, G. ““El costo social de las restricciones energéticas”.” El Universo., 2024, https://www.eluniverso.com/columnista/gabriela-calderon-burgos/.

CEPAL. (2024). Impacto del “Pico y Placa Eléctrico” en los costos operativos de las PYMES en Ecuador. Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe. https://www.cepal.org.

Cueva, A., y Torres, G. (n.d.). Energías renovables y adaptación empresarial en Ecuador. Revista de Gestión y Sostenibilidad. https://mediafra.admiralcloud.com/customer_609/23d7bd75-c1aa-451f-891e-ba122cb87bce?response-content-disposition=inline%3Bfilename*%3DUTF-8%27%27Okonomia-edicion02-nov2024-spread.pdf&Expires=1737510599&Key-Pair-Id=K3XAA2YI8CUDC&Signature=h5KGMBGXJDPT7fSa84.

Cueva, J., y Torres, L. (2024). Efectos económicos del "Pico y Placa Eléctrico" en las pequeñas y medianas empresas de Ecuador. Revista de Economía Ecuatoriana, 22(3), 33-45.

Dueñas, Ricardo. “Estrategias empresariales innovadoras ante la crisis energética.” Ekos Negocios., 2024, https://ekosnegocios.com/articulo/palabras-de-ricardo-duenas-en-expobienestar-2024.

ELIZABETH, IVONNE. “REPÚBLICA DEL ECUADOR MINISTERIO DEL TRABAJO ACUERDO MINISTERIAL Nro. MDT-2024-200 Abg. Ivonne Elizabeth Núñez Figueroa MINIS.” Ministerio del Trabajo. https://www.trabajo.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/ACUERDO-MINISTERIAL-NRO.-MDT-2024-200-signed.pdf.

Forbes. (2024, 15 de octubre). Pico y Placa Eléctrico: nuevas reglas laborales para enfrentar la crisis energética. https://www.forbes.com.ec/today/pico-placa-electrico-nuevas-reglas-laborales-enfrentar-crisis-energetica-n61435.

Gestión Pública. (2024). Limitaciones y propuestas para la supervisión laboral en Ecuador. Revista Administrativa. https://www.redalyc.org/journal/6955/695573791006/html/.

GK. (2024, 6 de noviembre). Pico y Placa Eléctrico: qué es y cómo afecta a la jornada laboral en Ecuador. https://gk.city/2024/11/06/pico-placa-electrico-explicado/.

González, J. M., y Sánchez, P. A. (2024). Adaptación de las empresas ecuatorianas a las modificaciones de la jornada laboral por el "Pico y Placa Eléctrico". Revista Latinoamericana de Derecho Laboral, 22(1), 50-65.

González, L., y Paredes, M. (2024). Comparación de incentivos energéticos en Colombia y Ecuador. Estudios Regionales en Energía. https://revistaenergia.cenace.gob.ec/index.php/cenace/article/view/176.

González, M., y Paredes, F. (2024). Políticas públicas para la transición energética: Lecciones de Colombia para Ecuador. Revista Internacional de Energía y Economía, 18(2), 59-72.

González, M., y Sánchez, P. (2024). El balance entre productividad y sostenibilidad en tiempos de crisis energéticas. Estudios Económicos Contemporáneos, 15(1), 88-104.

La Hora. (2024, 12 de diciembre). Pico y placa eléctrico: Solo el 2% de las empresas en Ecuador se acogió a la medida. La Hora. https://www.lahora.com.ec/pais/pico-placa-electrico-2-por-ciento-empresas-ecuador-acogio-medida/.

Lexis. (2024, 24 de octubre). Trabajadores en jornada especial por Pico y Placa Eléctrico recibirán pago por horas extras y suplementarias. https://www.lexis.com.ec/noticias/trabajadores-en-jornada-especial-por-pico-y-placa-electrico-recibiran-pago-por-horas-extras-y-suplementarias.

López, A. (2024, 28 de octubre). Normas jornada laboral crisis energética: Pico y placa eléctrico Ecuador. NMS Law. https://nmslaw.com.ec/blog/2024/10/28/normas-jornada-laboral-crisis-energetica-pico-y-placa-electrico-ecuador/.

Luzuriaga y Castro. (2024, Noviembre 25). La Falta de Electricidad en Ecuador: Impactos Legales y Económicos para las Empresas. Luzuriaga y Castro. https://luzuriagacastro.com/la-falta-de-electricidad-en-ecuador-impactos-legales-y-economicos-para-las-empresas/?utm_source.

Martínez Torrico, K. M., y Aliaga Lordemann, J. (2016). Introducción al estudio de la economía del sector energético (Documento de Trabajo No. 02/16). Instituto de Investigaciones Socio-Económicas (IISEC), Universidad Católica Boliviana "San Pablo". https://www.iisec.ucb.edu.bo/assets_iisec/publicacion/2016-2.pdf.

Martínez, L. P., y Torres, A. S. (2023). Impacto de las políticas de restricción vehicular en la productividad laboral: Un análisis de la implementación del "Pico y Placa" en Ecuador. Revista de Transporte y Desarrollo Urbano, 14(3), 120-135.

Meythaler y Zambrano Abogados. (2024, 22 de octubre). Pico y Placa Eléctrico: Modificación temporal de la jornada laboral. https://www.meythalerzambranoabogados.com/post/pico-y-placa-electrico-modificacion-temporal-de-la-jornada-laboral-ecuador.

Morales, A. B., y Castro, V. F. (2023). Impacto de la crisis energética en la organización del trabajo en Ecuador: El "Pico y Placa Eléctrico" como medida adaptativa. Estudios de Energía y Trabajo, 18(2), 45-59.

Pérez, C. R. (2022). La legislación laboral ante las restricciones de movilidad: El caso del "Pico y Placa" y sus implicaciones para los derechos laborales. Revista de Derecho y Sociedad, 30(4), 211-230.

Prado, Julio Jose. Ministerio de Producción Comercio Exterior Inversiones y Pesca – Ecuador, https://www.produccion.gob.ec/ . Accessed January 26 2025.

Primicias. (2024). Impacto del "Pico y Placa Eléctrico" en el ámbito laboral. Artículo digital. https://www.lexis.com.ec/noticias/por-los-cortes-de-luz-59-de-las-empresas-han-aumentado-sus-costos-operativos.

Primicias. (2024, 22 de octubre). Pico y Placa Eléctrico: Acuerdo ministerial permite modificar jornada laboral por cortes de luz en Ecuador. https://www.primicias.ec/economia/acuerdo-ministerio-trabajo-pico-placa-electrico-jornada-laboral-cortes-luz-ecuador-81793/.

Rodríguez, F. J., y López, M. D. (2024). Efectos de las políticas de restricción vehicular en el ámbito laboral: Estudio de caso en ciudades de Ecuador. Informe sobre el Impacto Ambiental y Laboral en el Ecuador, 10-25. https://www.ministerioambiental.gob.ec/informe2024.

Rosero, L. ““Impacto de las restricciones eléctricas en la productividad rural”.” Revista Coyuntura Económica, 36(2), 15-29., 2024, https://controlelectrico.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2024/09/Revista24-12sep.pdf.

Soria, R., Villamar, D., y Rochedo, P. (2024, Septiembre). Impacto económico de la transición energética en Ecuador. IDB-TN-3000.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.