|

(julio-diciembre 2025) Vol. 4 Núm. 2 ISSN (online): 2953-6596 |

Bioaccumulation and vertical transmission of microplastics within the poultry agri-food chain in Guayas, Ecuador

Bioacumulación y transmisión vertical de microplásticos dentro de la cadena agroalimentaria avícola en Guayas, Ecuador

Elsa Valle-Mieles1,2: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4738-7682

Douglas Pinela Castro 1: https://orcid.org/0009-0008-0237-7916

Gabriela Guevara Enríquez1: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0375-0758

Ricardo Solís-Villacrés3, https://orcid.org/0009-0006-2649-9868

Iván González-Puetate 1,2*: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9930-0617

1Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria y Zootecnia, Universidad de Guayaquil, Ecuador.

2Fauna, Conservation and Global Health Research Group, Universidad Regional Amazónica IKIAM – Ecuador.

3Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias, Universidad Estatal Península de Santa Elena, Ecuador.

*Autor correspondencia: ivan.gonzalezp@ug.edu.ec

Recibido: 24/noviembre/2025 Aprobado: 17/diciembre/2025 Publicado: 30/diciembre/2025

Es un artículo de acceso abierto con licencia Creative Commons de Reconocimiento-No Comercial-Compartir Igual 4.0 Internacional, lo que permite copiar, distribuir, exhibir y representar la obra y hacer obras derivadas para fines no comerciales y de revistas de OPEN JOURNAL SYSTEMS (OJS).

Resumen

El estudio evidenció que la presencia de microplásticos (MP) en la cadena avícola constituye un riesgo emergente para la salud animal y la inocuidad alimentaria, ya que estas partículas ingresan principalmente a través del alimento, el agua y el polvo ambiental, generando un proceso de bioacumulación progresiva. Mediante técnicas de flotación en NaCl y digestión alcalina se cuantificaron MP en alimento, heces, yema, saco vitelino y meconio, aplicándose análisis estadísticos como ANOVA, regresión lineal y agrupamiento jerárquico. Los resultados mostraron diferencias significativas entre matrices (p < 0.05), destacándose las mayores concentraciones en el meconio, seguidas del alimento y las heces, mientras que la yema presentó los valores más bajos, aunque biológicamente relevantes debido a la transferencia transovárica. Además, el modelo de regresión indicó una relación positiva entre el avance productivo y la acumulación de MP, y el dendrograma confirmó tres grupos: exposición intestinal, transferencia reproductiva y acumulación neonatal. En conjunto, estos hallazgos demuestran que los MP atraviesan barreras biológicas y se transfieren verticalmente desde la gallina hacia el embrión, lo que subraya la necesidad de implementar estrategias de control y monitoreo para reducir la exposición y proteger la seguridad alimentaria.

Palabras clave: transferencia vertical, inocuidad alimentaria, polímero.

Abstract

The study demonstrated that the presence of microplastics (MP) in the poultry production chain represents an emerging risk to animal health and food safety, as these particles enter primarily through feed, drinking water, and environmental dust, leading to a progressive process of bioaccumulation. Using NaCl flotation and alkaline digestion techniques, MP were quantified in feed, feces, egg yolk, yolk sac, and meconium, and statistical analyses including ANOVA, linear regression, and hierarchical clustering were applied. The results showed significant differences among matrices (p < 0.05), with the highest concentrations observed in meconium, followed by feed and feces, while egg yolk exhibited the lowest values, although these were biologically relevant due to transovarian transfer. In addition, the regression model indicated a positive relationship between production progression and MP accumulation, and the dendrogram confirmed three distinct groups: intestinal exposure, reproductive transfer, and neonatal accumulation. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that MP can cross biological barriers and be vertically transferred from the hen to the embryo, underscoring the need to implement control and monitoring strategies to reduce exposure and safeguard food safety.

Keywords: vertical transfer, food safety, polymer.

Introduction

Global plastic pollution has become a critical environmental issue worldwide. In this context, microplastics (MP; plastic particles smaller than 5 mm) and nanoplastics (NP; plastic particles generally <1 µm, including the nanometric range <100 nm) have gained increasing relevance due to their high surface area, enhanced physicochemical reactivity, and ability to cross biological barriers. These characteristics enable them to interact with ecological systems and disrupt biological processes across different trophic levels, potentially affecting organism health and ecosystem stability (Ahmad et al., 2025; Monclús et al., 2022).

The distribution of MPs and NPs has expanded beyond aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems, progressively reaching the agri-food sector. Within this context, animal production systems have been identified as relevant pathways of indirect exposure for human consumers, due to the incorporation of these contaminants into matrices such as water, balanced feed, and the production environment (Pinela Castro et al., 2025). In particular, poultry production represents a system of special interest given its high production intensity and close link to food safety.

In poultry production systems, microplastic ingestion occurs mainly through balanced feed, drinking water, and environmental dust. Available evidence suggests that these particles may compromise avian health by inducing alterations in intestinal integrity, inflammatory processes, and oxidative stress, while also raising concern regarding their potential systemic mobilization and transfer to reproductive organs (Carlin et al., 2020; Monclús et al., 2022).

Recent experimental studies have demonstrated that MPs and, especially, NPs can cross the intestinal barrier, enter systemic circulation, and accumulate in different tissues, including reproductive tissues. Considering that egg yolk formation depends on circulating precursors, the transovarian transfer of microplastics represents a plausible pathway linking environmental contamination to potential food safety–related risks and human exposure (Khan et al., 2024; Wu et al., 2021).

In Ecuador, primary information on the systemic accumulation and transfer of microplastics in animal production systems remains limited (Guanolema, 2024; Cárdenas & Valarezo, 2024). Nevertheless, recent investigations have reported the presence of microplastics in poultry production environments in the province of Guayas, evidencing their occurrence in birds from commercial systems and highlighting the need to deepen research in this field (Alvarado & Garnica, 2024; Yagual & Ricardo, 2024). These findings are consistent with documented evidence of MP contamination in environmental matrices such as rivers and coastal sediments, which act as indirect sources of contamination for the agri-food chain (Talbot et al., 2022).

In this context, the present study aimed to determine the presence of microplastics in the poultry production chain, generating baseline information to support risk analysis, food safety assessments, and the design of future environmental monitoring and management strategies.

Materials and methods

The study was conducted with the objective of quantifying and comparing the concentration of microplastics (MP) in several biological matrices along the poultry agri-food chain, encompassing the nutritional, intestinal, reproductive, and neonatal stages. The study population consisted of commercial laying hens and their derived products obtained from intensive and semi-intensive poultry production systems. The analyzed matrices included commercial feed, feces from young birds, feces from adult laying hens, egg yolk, yolk sac, and meconium from newly hatched chicks, allowing a comprehensive evaluation of MP distribution across the production continuum.

Microplastic separation followed a modified version of the Willis–Molloy method described by Guerrero et al. (2020). A supersaturated sodium chloride (NaCl) solution was used to promote differential flotation of plastic particles. For each sample, 2 g of material were mixed with 28 mL of the solution, homogenized using a glass rod, and incubated at 37.5 °C for four hours to allow low-density particles to rise to the surface.

The recovered supernatant was subjected to alkaline digestion to remove organic residues. Potassium hydroxide (KOH at 10%) was used for intestinal matrices (commercial feed and feces), whereas sodium hydroxide (NaOH at 10%) was applied to reproductive and neonatal matrices (egg yolk, yolk sac, and meconium). The mixtures were incubated at 37 °C for four hours, after which a 10 µL aliquot was extracted for microscopic examination at 10×–40× magnification. Morphological identification allowed classification of particles into fibers and fragments.

Microplastic concentration was expressed as particles per gram (MP/g) and calculated using the formula: MP/g = (Nobs × Vt) / (Va × Pm), where Nobs is the number of observed particles, Vt is the total volume of the supernatant, Va is the aliquot volume (10 µL), and Pm is the sample mass (2 g). This equation facilitated standardized comparisons across matrices. For egg yolk, concentrations were initially expressed as MP per unit and subsequently converted to MP per gram using the equation: MP/g = (MP per unit) / (average yolk weight). An average yolk weight of 17 g was used; therefore, a value of 10.2 MP per unit corresponded to 0.60 MP/g.

Statistical analyses were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to identify significant differences among matrices at a 95% confidence level. Duncan’s multiple range test (α = 0.05) was applied to determine homogeneous groups. All statistical procedures were carried out using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26.0, based on mean values of microplastic/g, fiber/g, and fragment/g for each matrix. Additionally, simple linear regression analysis was used to evaluate the association between the production stage (independent variable X) and microplastic concentration (dependent variable Y). Hierarchical cluster analysis (CA) was also performed using Ward’s method and Euclidean distance to identify similarity patterns among the analyzed matrices.

Results and discussion

In line with the results obtained, the intensification of modern poultry production has considerably improved feed efficiency, although it has also increased the exposure of birds to emerging contaminants such as microplastics (MP). These particles, which are characterized by a size smaller than 5 mm, originate mainly from polymer-based materials used in packaging, feed bags, piping systems, and other equipment employed in agro-industrial operations.

From a biological perspective, in laying hens, MP may enter the body through the formulated feed, drinking water, or airborne dust. Consistent with previous reports and supported by the present findings, once ingested, they can begin a gradual bioaccumulation process in digestive tissues and potentially reach the reproductive system. This situation has become a growing concern for human food safety because eggs, the primary product generated by this sector, may act as carriers of MP and the toxic substances that adhere to their surfaces.

Table 1. Risk levels associated with microplastic bioaccumulation and vertical transfer in the poultry production chain

|

Biological or production stage |

Matrix or Sample |

Bioaccumulation level and pathway |

|

Feeding and environment |

Commercial feed; environmental dust |

Surface exposure without tissue absorption; passive entry of external particles. |

|

Young birds (grower phase) |

Feces; intestinal content |

Intestinal bioaccumulation through adsorption and limited excretion. |

|

Adult hens (production phase) |

Feces; reproductive tissues |

Systemic bioaccumulation with possible migration via circulation. |

|

Breeder hens / fertile egg |

Egg yolk |

Transovarian transfer and vertical bioaccumulation. |

|

Newly hatched chicks |

Yolk sac; meconium |

Inherited and persistent bioaccumulation during embryogenesis. |

|

Commercial production (table egg) |

Yolk, albumen, eggshell |

Final stage of bioaccumulation and direct exposure route for consumers. |

Table 1 illustrates a progressive and continuous pattern of microplastic bioaccumulation throughout the poultry agri-food chain. Plastic particles originating from the environment and from feed constitute the initial point of exposure. In the early stages, commercial feed and airborne dust function as the primary sources of intake, where particles enter passively without direct tissue absorption. Although no immediate internalization occurs, continuous exposure leads to superficial accumulation within the digestive tract, gradually establishing a persistent plastic load.

As exposure persists, and as suggested by the observed accumulation patterns, microplastics adhere to intestinal microvilli and contribute to mucosal irritation and micro-lesions. These alterations increase epithelial permeability and facilitate the passage of particles into systemic circulation. This marks the shift toward a systemic form of bioaccumulation, in which particles may be transported to metabolically active organs and reproductive tissues, where they can remain for extended periods (see Table 1).

Taken together, these findings indicate that, in adult and breeder hens, this phenomenon becomes even more relevant due to evidence of transovarian transfer, meaning that microplastics can move from maternal blood into the ovarian follicle and ultimately into the egg yolk. During embryonic development, these particles may cross the vitelline membranes and reach both the yolk sac and the meconium, which demonstrates the persistence of the contaminant throughout embryogenesis. This pattern confirms the presence of a vertical mother-to-embryo transfer that connects environmental contamination with biological exposure and food-safety implications.

In the final stage, the table egg becomes the critical control point for food safety, as it serves as a direct vehicle of human exposure to microplastics. Overall, the information reflects an ascending gradient of accumulation that begins with feed and culminates in the final food product, underscoring the need for preventive actions in feeding, management and processing stages in order to safeguard food safety and consumer health (see Table 1).

Table 2. ANOVA results for microplastic, fiber and fragment concentrations (MP/g, F/g, Fg/g) and Duncan’s multiple range test at the 5% level

|

Stage in the production chain |

Matrix / Product |

Microplastics (MP/g) |

Total Fibers (F/g) |

Fragments (Fg/g) |

|

Feeding |

Commercial feed (poultry ration) |

5.0 b |

3.4 b |

1.6 b |

|

Young birds |

Feces from grower birds |

5.3 b |

3.4 b |

1.9 b |

|

Adult hens |

Feces from laying hens (ISA Brown) |

5.9 b |

3.8 b |

2.1 b |

|

Reproductive product |

Egg yolk (fertile or commercial) |

0.6 c |

0.4 c |

0.2 c |

|

Embryo |

Yolk sac |

4.7 b |

3.0 b |

1.7 b |

|

Neonatal |

Meconium (newly hatched chicks) |

6.6 a |

4.3 a |

2.3 a |

Different letters within each column indicate significant differences according to Duncan’s multiple range test (p < 0.05).

The analysis of variance (ANOVA), together with Duncan’s multiple range test at the 5 percent significance level, detected statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) in the concentrations of microplastics (MP), fibers (F), and fragments (Fg) across the various stages of the poultry production chain (see Table 2). The results indicate a progressive increase in bioaccumulation, starting with the initial phases of dietary exposure and continuing through the reproductive and neonatal stages.

According to Duncan’s multiple range test, statistically significant differences were identified among the evaluated groups. Egg yolk, classified within group c, showed the lowest concentrations of microplastics, although it remains relevant due to its role in transovarian transfer and its destination for human consumption. The matrices included in group b (commercial feed, feces from young and adult birds, and the yolk sac) exhibited intermediate and statistically similar values, reflecting continuous environmental exposure. In contrast, meconium, classified in group a, showed the highest concentrations (6.6 MP/g, 4.3 F/g, and 2.3 Fg/g), evidencing accumulation during embryonic development. Overall, the differences defined by Duncan’s analysis confirm bioaccumulation and the potential vertical transfer of microplastics along the poultry production chain (see Table 2).

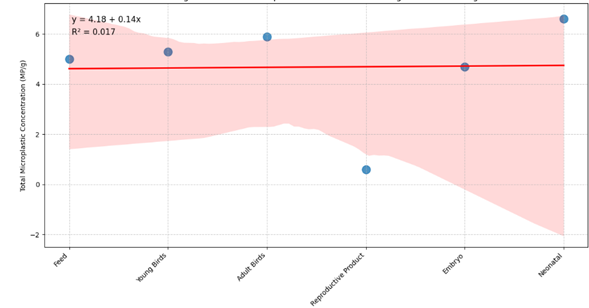

Figure 1. Relationship between production stage and microplastic concentration (MP/g) in the poultry agri-food chain according to the simple linear regression model

The simple linear regression analysis revealed a positive association between the production stage and the total concentration of microplastics (MP/g), suggesting a gradual pattern of bioaccumulation along the poultry chain. The fitted model was Y = 4.18 + 0.14X, where Y represents the estimated concentration of microplastics and X denotes the position within the production system. Although the slope was small (b₁ = 0.14), it indicates that each step forward in the biological sequence results in a slight increase in concentration. This pattern reflects an upward trend influenced by continuous exposure to particles during feeding and development.

However, the coefficient of determination (R² = 0.017) showed that only 1.7 percent of the variation in microplastic concentration is explained by the model. This finding reveals a weak association and suggests that the behavior of the data does not follow a strictly linear pattern. The discrepancy arises from the marked heterogeneity among matrices, particularly the low concentration observed in the reproductive product and the notably high value recorded at the neonatal stage.

Despite these limitations, the overall pattern shown in Figure 1 indicates that certain critical points within the chain experience a progressive increase in microplastic concentration. This tendency highlights a potential risk for food safety and consumer health.

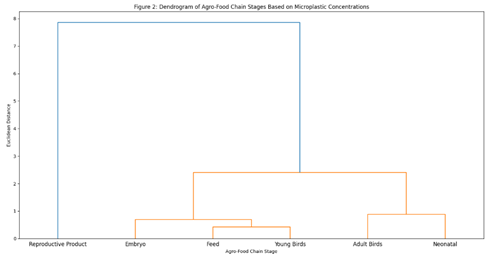

Figure 2. Dendrogram of similarity among poultry matrices based on microplastic, fiber and fragment concentrations (ward’s method).

The dendrogram arranges the stages of the poultry agri-food chain according to the numerical similarity of their microplastic concentrations, which makes it possible to visualize how matrices with comparable values cluster together. Lower linkage distances indicate higher similarity. The first cluster is formed by commercial feed (5.0 MP/g) and young birds (5.3 MP/g), whose values are nearly identical. Adult hens (5.9 MP/g) then merge with this cluster, maintaining a contamination pattern that is very similar to the initial matrices.

Neonatal meconium (6.6 MP/g) subsequently joins the group. Although its concentration is higher, it still falls within the general range of 5.0 to 6.6 MP/g, which reflects continuity in exposure. Slightly above this level appears the yolk sac (4.7 MP/g), which is close to the main cluster but different enough to be positioned at an intermediate linkage distance. Egg yolk (0.6 MP/g) remains fully isolated and connects to the rest of the matrices only at the highest Euclidean distance (approximately 8), indicating that its concentration is significantly lower and biologically distinct.

Overall, the dendrogram reveals three clear patterns. The first is a main cluster with concentrations between 4.7 and 6.6 MP/g. The second is an isolated matrix with very low concentration (0.6 MP/g). The third corresponds to an intermediate position represented by the embryonic stage. Together, these patterns illustrate the heterogeneity of microplastic accumulation across the chain and support the existence of differentiated exposure pathways.

The primary aim of this study was to quantify and characterize the presence of microplastics (MP) throughout the poultry agri-food chain, with particular attention to their vertical transfer into the egg and the neonatal stage. The widespread detection of MP across the system is consistent with global research, which identifies contaminated feed as the main source of exposure. The high concentrations observed in commercial feed (12,060 MP/kg) and the predominance of fibers and fragments point to pre-production vulnerabilities, most likely linked to packaging materials or raw-ingredient contamination (Khan et al., 2024).

The marked contrast between the low concentration detected in egg yolk (0.6 MP/g) and the comparatively higher levels documented in ingestion-related matrices (5.0–5.9 MP/g) suggests that the hen’s physiology may partially modulate, dilute, or limit the transovarian transfer of microplastics during vitellogenesis (Liu et al., 2022; Wu et al., 2021). Experimental and physiological evidence indicates that although microplastics are capable of crossing the intestinal barrier and reaching systemic circulation, their accumulation in reproductive tissues may be constrained by size-dependent translocation, selective uptake mechanisms, and metabolic processing at the ovarian level (Wu et al., 2021; Assersohn et al., 2021).

Nevertheless, the detection of microplastics in egg yolk confirms that the reproductive barrier is not fully effective. Even at lower concentrations relative to other matrices, their presence is biologically relevant given the yolk’s central role in embryonic nutrition and its direct contribution to human dietary exposure, reinforcing concerns related to food safety and maternal transfer of emerging contaminants (Khan et al., 2024; Alvarado & Garnica, 2024).

Furthermore, although fecal elimination is described as the primary route for the excretion of larger particles (>150 μm) (Wu et al., 2021), the elevated concentrations detected in feces indicate that birds remain under continuous exposure to environmental and dietary microplastics throughout the production system, which explains the sustained presence of these particles across the evaluated matrices.

The most critical finding emerged in meconium, which exhibited the highest concentrations (6.6 MP/g). This observation indicates that vertically transferred particles, likely nanoplastics or very small microplastics, accumulate efficiently in the embryonic digestive tract. Instead of being removed during development, these particles appear to concentrate within the organism, which highlights a case of neonatal bioaccumulation. This phenomenon raises concern regarding potential toxicological effects on chicks, particularly in relation to intestinal development and microbiota integrity (Monclús et al., 2022).

Overall, and from an integrated perspective, the study provides clear evidence of a vertical transfer pathway for microplastics in poultry under regional production conditions. Although the egg yolk may partially attenuate particle load, the final concentration found in neonatal meconium exceeds that of the matrices associated with initial exposure. These results call for an urgent toxicological assessment of MP in poultry systems, not only because of their implications for animal health but also because they represent an emerging risk to food safety.

Conclusion

The evidence gathered in this study demonstrates that microplastics are present at all stages of the poultry agri-food chain, from commercial feed to the meconium of newly hatched chicks. This distribution reveals a clear gradient of bioaccumulation across production stages and is consistent with the statistical patterns identified through ANOVA, regression analysis, and hierarchical clustering, thereby supporting the occurrence of vertical transfer within the poultry system under regional production conditions.

Although egg yolk exhibited the lowest microplastic concentration among the analyzed matrices, its detection confirms that the reproductive barrier does not completely prevent particle transfer. This finding is particularly relevant because egg yolk plays a central role in embryonic nutrition and constitutes a direct food product for human consumption, reinforcing its importance from a food safety perspective.

The elevated concentrations detected in meconium represent a key finding of this study, as they confirm the persistence of microplastics at the neonatal stage. Nevertheless, it is important to emphasize that neonatal assessment was limited exclusively to meconium. Consequently, the results do not allow direct conclusions regarding microplastic accumulation in embryonic tissues or the occurrence of specific physiological, intestinal, or microbiological effects. Parameters related to intestinal development, microbiota composition, and neonatal health were not evaluated, and any potential biological implications should therefore be interpreted with caution and within the context of previously published evidence.

Taken together, these findings highlight microplastics as emerging contaminants of concern within poultry production systems and demonstrate their ability to cross biological barriers and remain detectable across successive developmental stages. From a food safety and environmental health perspective, the results support the implementation of monitoring and control strategies for microplastics throughout the poultry production chain, within an integrated framework that includes prevention, surveillance, waste management, and regulatory compliance. Such actions are essential to mitigate exposure risks, protect consumer health, and strengthen the sustainability of poultry production systems.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: P.D., G.G., I.G.; Methodology: E.V., R.S., I.G.; Investigation: E.V., R.S., I.G.; Writing—original draft: P.D., G.G., E.V., R.S., I.G.; Writing—review and editing: G.G., I.G.; Supervision: P.D.

Referencias bibliográficas

Ahmad, S.,

Arshad, M. A., Ullah, A., Iftikhar, N., Sial, F. A., Qadri, R., & Sarwar,

M. (2025). Microplastic

pollution in the marine environment: Sources, impacts, and degradation. Journal of Advanced Veterinary and

Animal Research, 12(1),

260–279.

https://bdvets.org/JAVAR/V12I1/l893_pp260-279.pdf

Alvarado, M. L., & Garnica, A. P. (2024). Evaluación de la presencia de microplásticos en aves de producción en un cantón de la provincia del Guayas, Ecuador [Tesis de pregrado, Universidad de Guayaquil]. Repositorio Institucional UG.

Assersohn, K.,

Brekke, P., & Hemmings, N. (2021). Physiological factors influencing female

fertility in birds. Royal Society Open Science, 8, 202274.

https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.202274

Cárdenas Bermúdez, Z. A., & Valarezo Mora, C. A. (2024). Determinación de microplásticos en miel de abeja en colmenas del Zapotal, Santa Elena, Ecuador [Tesis de pregrado, Universidad de Guayaquil]. Repositorio Institucional UG.

Carlin, J.,

Biesinger, Z., & Pagen, I. (2020). Microplastic accumulation in the

gastrointestinal tracts in birds of prey in central Florida, USA. Environmental Pollution,

264, 114750.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114750

European Food

Safety Authority. (2016). Statement on the presence of microplastics and

nanoplastics in food, with particular focus on seafood. EFSA Journal, 14(6), 4501.

https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2016.4501

Guanolema Auquilla, L. M. (2024). Evaluación de la presencia de microplásticos en balanceado para aves de producción en Guayas, Ecuador [Tesis de pregrado, Universidad de Guayaquil]. Repositorio Institucional UG.

Guerrero, S. F., Sánchez, M. A., & Lomas, V. E. (2020). Metodología para la detección de microplásticos en matrices biológicas avícolas [Manuscrito no publicado]. Universidad de Guayaquil.

Khan, F., Chen, J., Li, Y., Wang, F., Hussain, N., Shahzad, M. R., & Wang, Y. (2024). Harmful impacts of microplastic pollution on poultry and biodegradation techniques using microorganisms for consumer health protection: A review. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology, 107, 104523. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.etap.2024.104523

Kutralam-Muniasamy, G., Pérez-Guevara, F., Prata, J. C., Costa, J., & Malafaia, G. (2023). Microplastics: A real global threat for environment and food safety: A state of the art review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 3122. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043122

Liu, Y., Wu,

S., Jiang, W., Dai, X., & Cheng, Y. (2022). Microplastics contamination in

eggs: Detection, occurrence and status. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 439, 129654.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.129654

Malafaia, G., & Barceló, D. (2023). Toxicity induced via ingestion of naturally-aged polystyrene microplastics by a small-sized terrestrial bird and its potential role as vectors for the dispersion of these pollutants. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 424, 127753. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.127753

Monclús, P.,

Carlin, J., Sarda, L., & Prata, J. C. (2022). Birds as bioindicators:

Revealing the widespread impact of microplastics. Toxics, 6(1), 10.

https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics6010010

Naz, A., Javid,

A., & Ahmad, S. (2024). The sources and impact of microplastic intake on

livestock and poultry performance and meat products: A review. Animals, 14(4), 612.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14040612

Pinela Castro,

D., González-Puetate, I., & Valle-Mieles, E. (Eds.). (2025). Presence of microplastics in

livestock production: A challenge for animal health and sustainability.

Deep Science Publishing.

https://doi.org/10.70593/978-93-7185-104-6

Prata, J. C.,

& Dias-Pereira, J. (2023). Polystyrene nanoplastics exposure alters gut

microbiota and correlates with egg quality parameters in chickens. Animals, 15(21), 3154.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15213154

Talbot, R.,

Cárdenas-Calle, M., Mair, J. M., López, F., Cárdenas, G., Pernía, B., Hartl, M.

G. J., & Uyaguari, M. (2022). Macroplastics and microplastics in intertidal sediment of Vinces and

Los Tintos rivers, Guayas Province, Ecuador. Microplastics, 1(4), 651–668.

https://doi.org/10.3390/microplastics1040045

Wu, X., Zhang,

T., Chen, H., Chen, R., & Li, M. (2021). Microplastic ingestion by broiler

chickens. Environmental Pollution, 277, 116812.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2021.116812

Yagual, D. E., & Ricardo, D. E. (2024). Evaluación de la presencia de microplásticos en pollos nacidos de tres tipos de reproductoras en dos sistemas de producción [Tesis de pregrado, Universidad de Guayaquil]. Repositorio Institucional UG.