Ramón Estrada(a, b), César Morab,

aPolytechnic University of Durango, Durango-Mexico Highway km 9.5, Durango, Dgo, ZIP Code 34300, México.

bResearch Center for Applied Science and Advanced Technology, Legaria Unit of the National Polytechnic Institute, Legaria 694, Miguel Hidalgo, ZIP Code 11500, Mexico City, Mexico.

Corresponding author: cmoral@ipn.mx

Vol. 04, Issue 01 (2025): July

ISSN-e 2953-6634

ISSN Print: 3073-1526

Submitted: December 4, 2024

Revised: December 19, 2024

Accepted: June 24, 2025

Estrada, R. F., & Mora, C. (2025) Experimental video in Physics: a complement to hybrid teaching EASI: Engineering and Applied Sciences in Industry, 4(1), 11–22. https://doi.org/10.53591/easi.v4i1.1911

Articles in journal repositories are freely open in digital form. Authors can reproduce and distribute the work on any non-commercial site and grant the journal the right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

The quarantine closed schools in response to the rapid spread of COVID-19, posing among the risks to high school education, the increase in the educational gap. We present research on how school closures in 2020 influenced student performance when using videos for teaching physics based on the curriculum. Data from 69 fourth-semester students who performed various exercises with mathematical problems were analyzed and it was found that student performance did not increase significantly during school closures in 2020. However, the analysis also suggests a reduction in the achievement gap between low- and high-performing students.

Keywords: Learning, Performance, Physics, Performance.

La reciente pandemia global provocada por el COVID-19 llevó al cierre de escuelas en todos los niveles educativos, implementándose simultáneamente el aprendizaje a distancia. Resulta interesante analizar lo ocurrido después del periodo de aislamiento social, así como los resultados positivos que dejó la emergencia sanitaria en la educación en ingeniería. Se presenta una investigación sobre cómo los cierres escolares en 2022 influyeron en el rendimiento estudiantil al utilizar videos para la enseñanza de la física basada en el currículo. Se analizan datos de 69 estudiantes de cuarto semestre que realizaron diversos ejercicios con problemas matemáticos, y se encontró que el rendimiento estudiantil no aumentó significativamente durante los cierres escolares de 2022. Sin embargo, el análisis también sugiere una reducción en la brecha de rendimiento entre estudiantes de bajo y alto desempeño.

Palabras claves: Aprendizaje, Desempeño, Física, Rendimiento.

The teaching of Physics at the Upper Secondary Level (NMS) in Mexico is considered a problem derived from the low disposition of students towards this area and the low enrollment of graduates who decide to study this field at the higher level, much of this has been attributed to the teaching practices of teachers, which leads to apathy and indifference of students, not to say, hatred of the subject (Puentes, 2012). During these almost two years of pandemic from March 2020 to February 2022, work was carried out at the Centers for Industrial and Services Technological Studies (CETIS) in Mexico City and Durango, virtually through various platforms in which oral presentations predominated, supported by online books, videos, PowerPoint presentations, which we call the new traditional class, only electronically since if the oral presentation was the previous one, now this form of presentation was the norm and almost the only one. If we add the lack of control over students' activities behind the screen to the aforementioned apathy, we observe that these activities do not engage students. Therefore, to combat both disinterest and poor learning, from the early stages of the pandemic, demonstration experiences were carried out during videoconference sessions. In addition, students were asked to carry out experiments at home with easily accessible materials, and it was considered that they could reconstruct previous concepts already covered in class. As a result, we found students who carried out the activities to the best of their ability; others tried to do them under the conditions; some argued: not having been able to connect, not understanding the instructions, not even having obtained the materials, or not attending regularly.

In this way, a certain group of students could not be evaluated due to lack of attention, connection, materials, and/or attendance, forcing the opening of other options. Among them was the platform's ability to record the class at any time, allowing students who had not connected for any reason to do so when they could. They were then asked to review the recordings to complete activities or make up for missed classes. The problem arose again since each recording lasted an hour and a half, so if they didn't have time for the regular class, it was more difficult to watch them outside of class. Reviewing the materials and trying to make them more accessible, the idea arose to remake the recordings of the class topics into demonstration videos that were made at home, resembling what the student had to repeat and test, but in the form of capsules, in less time, and only solving one topic at a time. This way, the student could follow the sequence of the demonstration and, in turn, complete it at home. Thus, each video was designed and created to fulfill a construction process, in which the student, based on trigger questions, is led through a process of inquiry, reasoning, and reflection. This process is then used to answer these questions and, using the elements of the experimental demonstration, add them together and construct the concept, both verbally and mathematically, based on the numerical relationship or proportion found in the experience. In the end, the student is able to verbalize the statement and move from cognition to metacognition. That is, to appropriate the knowledge, reproduce it, and teach it to their peers, verifying it with the facilitator. The three teaching methods tested were evaluated: traditional lecture, student practice, and the use of video. A statistical analysis was performed using a Google Forms form (sent by email to their institutional account) to determine whether there is a difference between the teaching methods.

The teaching of experimental sciences at the General Directorate of Technological and Industrial Education (DGETI) has been researched a little. There are national studies on EMS such as those by Alvarado (2014) or Hernández and Benítez (2018). From the few existing indicators and derived from experience in this field, we identify that there are many students with serious learning problems in Physics, at least at the campuses in Mexico City and Durango, as has been discussed at the meetings of the State Academy of Physics. Despite programs such as Construye-T, Tutorías, or No Abandonment, which attempt to anticipate students falling at risk of high failure rates, combined with adverse socioeconomic conditions and the multiple problems arising from social isolation, we find students who fell into high failure and/or dropout rates. A first approach to identifying the problem which this paper attempts to address is that teachers in this area come from very diverse professional backgrounds, with little or much experience in teaching. However, what is common is the lack of appropriate didactics in teaching experimental science such as physics. They have not completed any postgraduate studies in didactics or education, much less ventured into educational research. Despite the inter-semester refresher courses offered by the DGETI (National Institute of Statistics and Census) or the Sectoral Coordination for Academic Strengthening (COSFAC), few of these courses are aimed at teacher refresher courses in this discipline (see the website of the National Center for Teacher Development (CNAD) (https://cnad.edu.mx) or the COSFAC (http://cosfac.sems.gob.mx). The teaching practices followed by teachers are derived from their professional experience or from the teaching models of their professors during their student years (Sánchez, 2009).

Delimiting the problem's approach to physics is a consequence of the traditional approach to teaching physics and the lack of didactics in experimental sciences. Thus, this proposal for the use of video as a collaborative tool or alternative to traditional teaching emerges, a teaching strategy available to both students and teachers. Our assessment of this problem focuses, rather than on reducing failure or dropout rates, on changing students' attitudes toward physics, allowing for immediate individual learning and subsequent collaborative learning. In addition to recognizing and developing their basic and higher cognitive processes, the current attitude reduces completion efficiency in the NMS and graduate enrollment in higher education institutions in this field.

Has the lack of didactics in experimental sciences, as well as the limited use of strategies that develop cognitive and metacognitive processes, caused students to experience indifference and apathy toward science, and especially physics, bordering on phobia?

Will the use of guided experimental demonstration video be able to How can we modify students' attitudes toward physics and develop their cognitive processes and recognize metacognitive ones?

By comparing the results below with the forms administered to students using the video versus traditional lecture and student practice, we will be able to provide an objective interpretation supported by statistical analysis.

The first reason for conducting this research is the authors' personal motivation. After years of dedication to this field, they find that students' willingness and the knowledge they have at both entry and exit levels are increasingly declining. The amount of content has been reduced, as has the depth of its coverage. The pandemic opened an alternative to modify teaching strategies, including the one now presented, in the quest to improve the teaching-learning process.

The second reason is aimed at students and teachers: students reconsider their approach to Physics, to see that they are capable of learning and constructing, and teachers to have alternatives and/or develop them themselves, seeking ongoing training as self-taught individuals.

In addition to conducting this research as a teaching alternative, we believe it should be done to change students' attitudes toward Physics. It should also help teachers see a different way of working, encouraging them to modify their strategies and thinking patterns, and to build their own materials. A recurring complaint among them is the lack of materials or laboratories. However, by using creativity, as shown here, they can replace them. Providing teachers with more support for their teaching practice can improve their teaching, making it less traditional and more accessible to students, thus improving their expectations and attitudes. Among the benefits to be obtained are convenience, first of all, 1) because it is a strategy that was used during the pandemic; 2) its availability when required; 3) increase teachers' strategies to modify their teaching practices, and 4) provide another opportunity to students who cannot access them due to reasons stemming from the pandemic itself, such as the economic difficulties many of which lead to a lack of connection, data, or time, due to working to support their families and homes.

The social relevance of using videos will develop students' self-confidence, increasing their self-esteem as they realize they learn and build on their own. They will also be able to recognize how they learned and how they regulated their metacognitive processes. This will not only be useful in this field but also has the practical implication of giving them the opportunity to pursue, upon graduation, areas of knowledge such as Physics itself or engineering, areas that are under-demanded at universities, but where the country requires these types of professionals for its development and that of science. The theoretical value of this research lies in pedagogy and didactics, because it is designed to develop higher cognitive and metacognitive skills. The sequence of activities within the video affects the student's mental and material participation so that they combine and complement each other in this development, in combination with methodological usefulness, through having a method for collecting evidence to evaluate this development, such as the creation of videos by the student showing their progress.

General Objective: Teachers will be able to design new learning strategies, transform their teaching practice and create didactics that stimulate the mental and procedural construction process of students taking Physics 1 at CETIS 56, 76, and 148.

To evaluate students' attitude, change and learning achievement using video, measuring these advances, the degree of interest and participation it arose in students, as well as any learning obstacles on a Likert scale. To compare students' progress in construction and conceptual, verbal, and mathematical formulation based on classroom experiences, demonstrating their cognitive and metacognitive development derived from the use of videos versus traditional lectures or student practice during the second semester of 2022/2023, and statistically discriminating their differences. The teacher will be able to propose new strategies, adapting, modifying, or designing teaching methods in pursuit of the above objectives, convinced, first and foremost, of his transformative role.

According to Blakemore and Frith (2011), the idea that the brain develops until childhood has been left behind. The frontal cortex continues to develop throughout adolescence, making it necessary to extend the educational stage to continue shaping it during those troubled years of adolescence and strengthening internal control. Furthermore, their behaviors are explained by a learning mechanism: imitation, but selective, influenced by peers.

Thus, we believe that the use of video under the conditions we establish is a vehicle that leads to a process of construction and learning, and above all, growth. According to Ortega et al. (2019), young people live in an environment in which the media stimulates them, and their senses are exposed to a multitude and variety of sensations and their representations, allowing them to learn more and more easily, fostering multiple intelligences. The use of video creates empathy by situating learning experiences in real life, strengthening communication skills. Therefore, we ask that students create a video where they demonstrate their learning verbally and in writing. As Rodríguez et al. (2015) point out, video can be used in pedagogical or teaching contexts, given the ability to record events of teaching interest and reproduce them as many times as necessary, which is its main advantage. Expressive or playful videos are recommended for teaching through play. In our case, interactive video at the upper secondary level allows students to participate in this game, while also obtaining information for the construction of theoretical concepts, both written and verbal, and mathematical formulations. According to Rodríguez et al. (2015), symmetrical and reciprocal communication is established; its repetition and reconstruction consolidates the content.

According to Sánchez (2018), many teachers use videos but do not produce them due to lack of interest, methodologies, or a work plan. Our model is the 5 E's (Bastida-Bastida, 2019), proposed by the Biological Sciences Curriculum Study (BSCS), a combination of instructional models such as Herbart's, Dewey's, and the Atkin-Karplus learning cycle. Bastida's experience trained teachers to develop their competencies using the 5 E's model, which will allow them to significantly expand, transform, and improve their teaching practices, changing their attitudes, open to change and the expectation of new possibilities, to the innovation of educational practices, and to the desire to learn more and to learn more about other ways of teaching and learning. To enter and complete a scientific career in engineering, motivation and willingness are essential. These should be instilled during adolescence and the student's time in higher education. In Mexico, admissions mechanisms must be approved, and this option must be available in higher education (HE) in their area. However, the lack of motivation in higher education requires finding methods to make learning at this stage more rewarding (Blakemore et al., 2011). In their words, selective attention, decision-making, and response inhibition skills, along with the ability to multitask, are skills that could be improved in adolescence.

According to Jiménez (2019), the aim is to use high-potential videos, that is, those that meet the learning objectives, can transfer all the content, and are easy to understand and remember without the need for direct, personal intervention from the teacher. The narrative is understandable and sequential, and in our case, orienting the interaction towards the development of the skills we have proposed. The creation of videos with this potential and quality constitutes them as educational videos. Rodríguez et al. (2017) propose the task of designing teaching strategies to be leveraged in the educational field, expanding the possibility of going beyond the classroom, optimizing the time of the school day. However, it is necessary to demonstrate their effectiveness in improving educational quality and stimulating student interest, stimulating group discussion, working from different perspectives on a topic, and being favorable in distance education or in conditions such as the current ones, where learning networks are spaces for debate, consensus, and construction. Jiménez et al. (2018) indicates that the sequential form of video construction and its availability allow students to carry out activities, regressing when they do not understand something and advancing at their own pace and needs, resorting to repetition as many times as necessary.

Learning occurs by logically presenting the concepts.

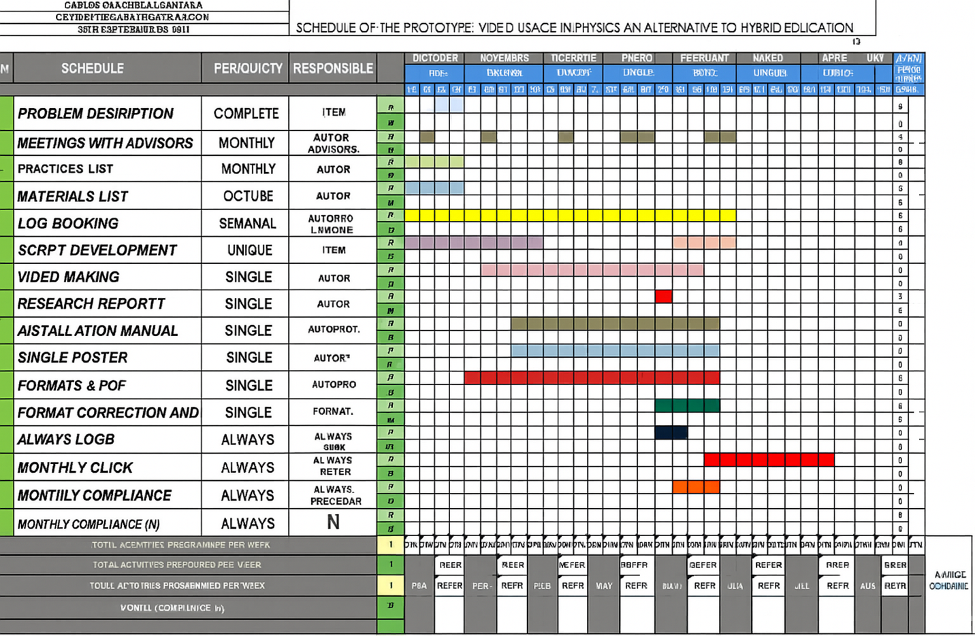

The Gantt chart shows the sequence of processes and activities. Key processes are indicated in bold italics, and are shown after the diagram and resources, following Bardin's (2002) Methodological Path (see Figure 1).

As explained in the problem statement, this arose as a teaching need or alternative due to a health emergency, in addition to offering an alternative to students affected by it. Thus, during the months of September and October, the recordings of the daily classes served as a model for this work. We were able to use the months of December and January to improve and adjust both the video and the other materials, so we can estimate a timeframe of 5 months or 20 weeks until the submission and upload of documents, which was due on February 28th.

The material resources used during the video are average household materials, reusable, and were not considered an additional financial burden. This is one of the additional purposes of this work: to enable the practices to be carried out without the need for a laboratory and special equipment. As indicated above, the financial resources required were minimal and were used to purchase three or four balloons, perhaps a syringe, and a pair of rubber bands; this does not generate an expensive expense. The equipment did require the use of a cell phone to record the videos, but it could be any type of video, with or without data. The video editor could then be downloaded for free, or it could be pre-installed on the computer, such as Windows Movie Maker or iMovie.

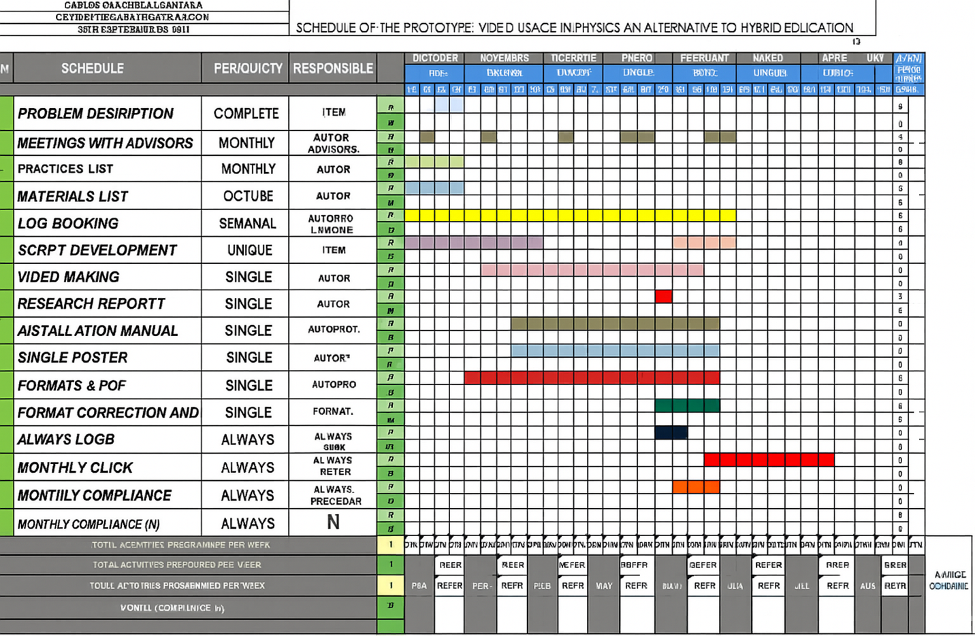

It should be noted that the Methodological Path required by Bardin (2002) is applied to Content Analysis. In his words, "it is the identification and explanation of the cognitive representations that give meaning to every communicative narrative. The aforementioned techniques can be applied to the analysis of texts, generally written texts produced by the mass media." This is a path for a specific type of analysis and has been adapted to this report, since we did not analyze the content of a text, although the students' open-ended responses were categorized (see Figure 2).

The impact of this work sets it apart from the videos available on platforms and websites (there could be thousands). Many of them are recorded lectures of a teacher writing on a blackboard or screen or working through problems step by step on the board or using spreadsheets like Excel, but they are still demonstrations of the teacher's knowledge. The intended innovation is that the self-directed video will lead the student to achieve learning, based on the following characteristics not found in existing videos and that these translate into benefits for the student, as indicated in the key:

| Trigger question that stimulates inquiry Logical content established in a script Construction process and progressive sequence of activities Increasing and linked learning paths Materials management Procedural skills Data collection, management, and arrangement in tables |

|

Independence Discipline Development of cognitive processes Self-construction of knowledge Development of logical and critical thinking Contextualizes with their experiences Incorporates it into the field of basic sciences, fundamental for the management, use, and conservation of resources A person with critical thinking capable of arguing based on logic and science Recognition of their abilities Self-esteem |

The information consulted, already mentioned, leads us to the characteristics that videos should have: The content is presented in a logical but flexible manner, the construction and sequence of activities is progressive, as is cognitive development stimulated by images and materials, their interaction with them makes them participate in the creation of significant results and learning, placing them in their daily lives. A difference can be seen with internet videos about science, which do not meet similar characteristics or are similar. Hence, we consider this work to have a high degree of innovation, as it is designed with the development of students' skills, their participation and interaction, and their ability to self-assess and recognize their learning and the processes that led to it.

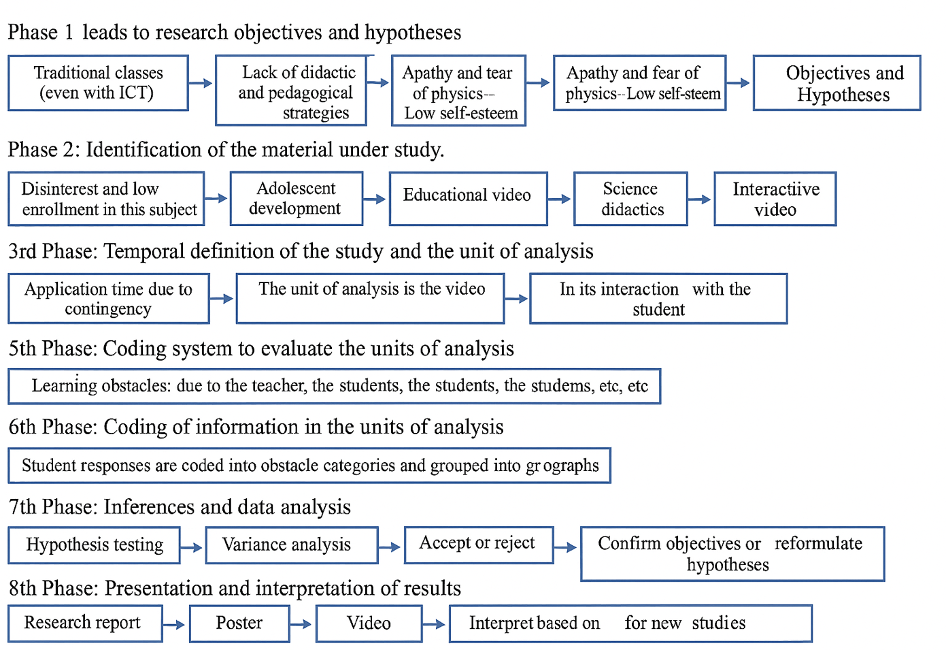

The graph in Figure 3 shows the technical conception for making the video (Sánchez, 2018). The information consulted, previously mentioned, leads us to the characteristics that videos should possess: The content is presented in a logical yet flexible manner; the construction and sequencing of activities is progressive, as is cognitive development, stimulated by images and materials. Their interaction with them makes them participate in the creation of meaningful results and learning, placing them in their everyday lives. A difference can be seen with online science videos that do not meet similar or even similar characteristics. Therefore, we consider this work to have a high degree of innovation, considering the development of students' skills, their participation and interaction, and their ability to self-assess and recognize their learning and the processes that led to it.

These elements involve pre-production, from the conception of the idea, the content, the objectives to be developed, the sequence of progressive activities, the emphasis on the cognitive processes to be stimulated, the script, the materials used, the actual production and execution of the video, and the final details in post-production, primarily its editing and, once finished, its upload to social media and online publication. The equipment indicated in the graph by Sánchez (2018) would be optimal, accompanied by a production team; in our case, it was minimal, but with the utmost attention to detail to ensure a quality product. Except for the Switcher software and the recorders, everything was personal equipment and family advice.

Therefore, the degree of feasibility, both technically and financially, is very high; what is lacking is the feasibility of the teaching staff. We can say that the cost is on time, but it is nothing if the activities are carried out within the school, as part of the semester's activity schedule and with the support of the authorities of each school. The implementation of this work is intended for whom we offer it and for whom we work: the students. Giving them tools for their personal and academic development, which implies better preparation, change of aptitudes and attitudes towards school, study, science and life, a desire for improvement and preparation to face higher education, especially in these areas of science and having better citizens, better professionals for the development and management of resources.

In the previous point, we already indicated part of the social impact of this work, not so much in terms of the video itself, but rather as an alternative for both teachers and students to grow and believe in themselves. Teachers are empowered by the ability to create materials and innovative, creative, and interactive experimental practices that serve the student's growth and maturation process, modifying their praxis by offering teaching strategies based on a communicative pedagogy supported by constructivism and the inquiry model. This translates into a change in student attitude toward this discipline and toward science in general, by introducing them not to it through a rote learning process, but rather through the recreation and reconstruction of concepts through experience, as a set of activities that modify their thought structures and allow them to grow, create, and ultimately increase their self-esteem by realizing their learning. The social impact, seen in this way, is the development of students with a different perspective on school and education, who upon graduation are prepared to enter higher education (HE), specifically within the fields of science and engineering. Their activities contribute to their personal well-being, and their actions contribute to that of the society in their context.

The skills, knowledge, and attitudes acquired foster their participation in a knowledge society, both in the workplace and in society. This is achieved within a framework of equity, flexibility, comprehensiveness, and openness, which contributes to meeting the country's social and economic needs. By promoting the development of critical professionals committed to society and the environment, and by generating knowledge through scientific research and technological innovation that contribute to the country's sustainable development.

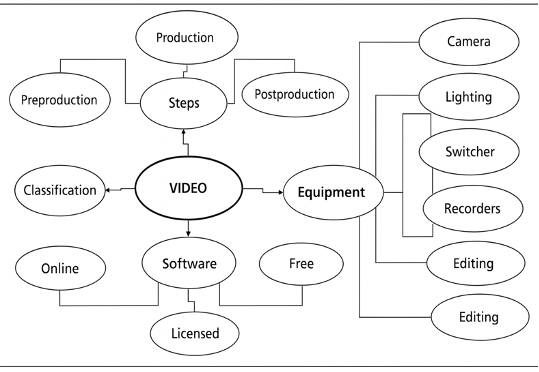

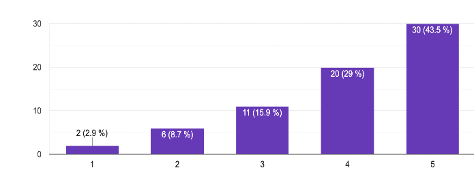

Triangulation: The results were obtained through a questionnaire completed by 69 students, evaluating three questions (A, B, and C) regarding the learning obtained. A represents a normal class (professor lecturing); B represents the student performing the practice independently following the professor's instructions; and C represents reviewing prototype videos, rating themselves on a Likert scale of 1 to 5 (1 = none, 2 = a little, 3 = average, 4 = most, and 5 = all). To triangulate the above, two open-ended questions were added in which students explained the reasons that made learning difficult for them in the best and worst cases.

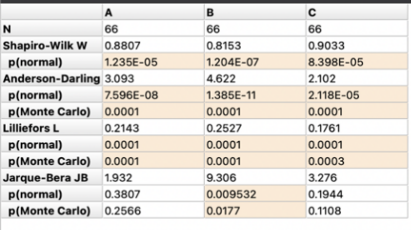

Normality and homogeneity of variances. The Shapiro-Wilkinson test tells us that the data do not follow a normal distribution, the p value is greater than .05 (Figure 4), so an ANOVA is not appropriate, but rather the Kruskal-Wallis test. Even so, we apply both to test the null hypothesis (H0), since as the sample size increases the data normalized.

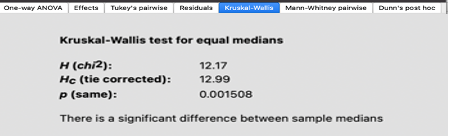

Difference in means: In Figure 5, the Kruskal-Wallis test indicates that if there is a difference in at least one of the means of the three treatments applied, A, B, and C, the hypothesis H0 of no difference between treatments is rejected.

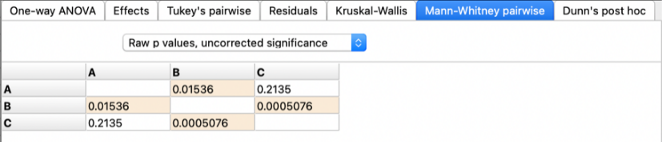

Figure 6 shows the paired data from Mann Whitney, indicating that the difference is between A with B and B with C, that is, normal class versus practical class and practical class versus video.

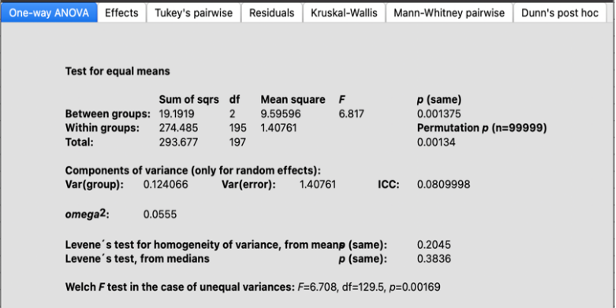

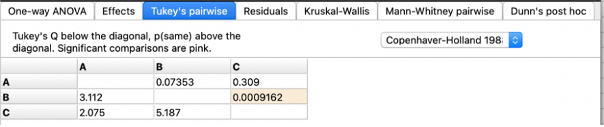

The ANOVA test (Figure 7) gives us a p value less than 0.05, which confirms the rejection of H0 and that there are differences between the treatments, only in this case the Tukey test indicates a difference between B and C (Figure 8).

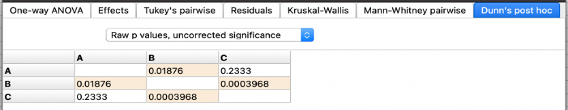

Confirmation of the Kruskal-Wallis test is given by the Dunn test (Figure 9), for non-parametric data, such as those used in the form scale, that is, there are differences in the perception of learning when students receive the class from the teacher and when they do the practices on their own, and also a difference between the students' practices and watching the videos.

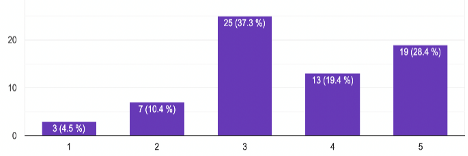

Figure 10 shows that 48% of young people learn most or all of the teacher's class, but 37% is barely enough and 15% little or nothing.

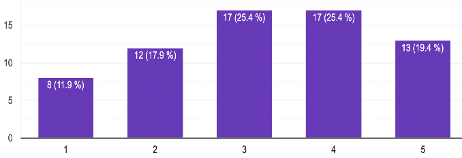

In Figure 11, we see that 50% of the learning experience falls between sufficient and good, and when added together, the total increases to 70%. These data show a more normalized distribution.

In Figure 12, it's important to highlight that more than 72% learn most or all of the subject matter by doing things on their own, while only 12% learn little or nothing. This reinforces the fact that education shouldn't be tied to a single strategy; that's why we emphasize the collaborative aspect among them, but we emphasize that they grade better when they do it on their own.

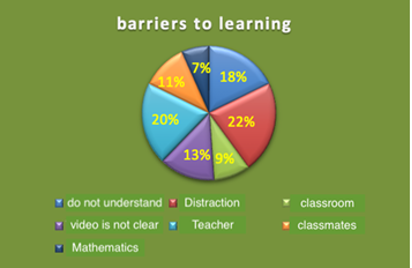

The open questions were grouped into categories with respect to the obstacles to their learning and are shown in Figure 13, in which we see that the main obstacles are:

Although 22% of students consider distraction as the main cause, followed by the teacher's actions in the exercise of their praxis, we observe that all obstacles are linked to the action and inaction of the teacher, their planning, the design of strategies, the use of teaching materials or not, triggers this sequence of obstacles, hence, they continue to be the main person responsible for managing the teaching-learning process and for which they must be permanently prepared.

The first conclusion drawn from the above is that the teacher remains the primary actor and responsible for student learning, the conditions under which it occurs, and the planning, design, and execution of their practice.

The use of high-potential videos, as indicated by Jiménez (2019), is capable of increasing learning compared to in-person classes. We still need to provide guidance and be more precise in our instructions, as some students indicated. Furthermore, there is no teacher intervention, so interaction with the video leads to the development of skills and the achievement of learning.

The sequential construction of the video allowed students to return to it as many times as necessary and advance at their own pace, as proposed by Jiménez et al. (2018). And when presented logically, relating them to students' preconceptions, they are relevant to the development of their cognitive structure, and significant learning occurs, according to Eslava (2018) and Figure 2, which shows the trend toward normalization. We also conclude that the aspects of disinterest, apathy, failure, and low enrollment (due to dropout) are largely due to teaching practice; the prototype presented is only a small effort to modify it. According to Sánchez (2018) and Bastida-Bastida (2019), promoting techniques or workshops for creating materials is advisable and necessary. Using the methodology followed here and offering a product that engages students by combining different instructional models and diverse teaching strategies would allow the discipline and teachers to recover the value and prestige they have lost.

César Mora thanks the National Polytechnic Institute for the support received through SIP project 20242422 and the National System of Researchers.

Alvarado, Z. C. (2014). La Enseñanza y el Aprendizaje de las Ciencias Experimentales en la Educación Media Superior de México. Ensino das Ciências da Natureza na América Latina, 2(2). Disponible en: https://revistas.unila.edu.br/imea-unila/article/view/343

Bardin, L. (2002). Análisis de contenido. Madrid, España. Ed. Akal, https://books.google.com.pe/books?id=IvhoTqll_EQC&printsec=frontcover&hl=es#v=onepage&q&f=false

Bastida-Bastida, D. (2019). Adaptación del modelo 5E con el uso de herramientas digitales para la educación: propuesta para el docente de ciencias. Revista Científica, 34(1), 73-80. Doi: https://doi.org/10.14483/23448350.13520

Blakemore, S-J. & U. Frith. (2011). Cómo aprende el cerebro. 3ª reimpresión, Ariel. ISBN: 8434413132/9788434413139.

Eslava, M. Á., O. López, H. L., Vidaurre, W. E. (2018). Videos educativos como estrategia tecnológica en el desempeño profesional de docentes de secundaria. Revista Venezolana de Gerencia, 23 (84), Universidad del Zulia, Venezuela. Disponible en: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=29058776019

Hernández, M. Á., Benítez, A. A. (2018). La enseñanza de las ciencias experimentales a partir del conocimiento pedagógico de contenido. Innovación educativa, 18(77), 141-163. http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1665-26732018000200141&lng=es&tlng=es

Jiménez, R., Sarmiento, M. (2018). Videos tutoriales para fortalecer la enseñanza-aprendizaje de la asignatura de computación en estudiantes de 5° año de la “Columna Pasco”. Tesis. U. N. D. A. C. Perú. Doi: http://repositorio.undac.edu.pe/bitstream/undac/285/1/T026_70874423_T.pdf

Jiménez, B. T. B. (2019). Los videos educativos como recurso didáctico para la enseñanza del idioma ingles. Tesis. Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar. Quito. Ecuador. https://repositorio.uasb.edu.ec/bitstream/10644/6988/1/T2994-MIE-Jimenez-Los%20videos.pdf

Lira-da-Silva, R. M., Rodrigues, M., Menezes, M., Bortoliero, S. T. (2018). A produção de vídeos educativos sobre ciências com estudantes de licenciaturas: os professores comunicam. Enseñanza de las ciencias. Revista de Investigación y Experiencias Didácticas, pp. 1845-50. https://raco.cat/index.php/Ensenanza/article/view/337494

Ortega, I., Rincón, G., Hernández, C. (2019). Uso del video como estrategia pedagógica para el desarrollo de la competencia escritora en estudiantes de educación básica. Revistas Perspectivas, 4(2), 52-63. Doi: https://revistas.ufps.edu.co/index.php/perspectivas/article/view/1972

Puentes, A., Cruz, I. M. (2012). Innovación educativa: implementación de la física introductoria en la modalidad semipresencial. Pixel-Bit. Revista de Medios y Educación, (40), 125-136. ISSN: 1133-8482. Disponible en: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=36823229010

Quito-Peralta, Á., Álvarez-Lozano, M. (2021). Powtoon como estrategia de enseñanza en Ciencias Naturales en la Básica Superior. CIENCIAMATRIA, 7(13), 103-121. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.35381/cm.v7i13.474

Rodríguez, D., D. Pedraza, M., Aria, E. C. (2015). El video. Su utilización como medio de enseñanza en las ciencias naturales. Estudios del Desarrollo Social. Cuba y América Latina, 3(1), 74-83. Disponible en: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=552357190005

Rodríguez, R. A., López, S., Mortera, J. (2017). El video como recurso educativo abierto y la enseñanza de matemáticas. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 19(3), 92-100. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.24320/redie.2017.19.3.936

Sánchez, A. C. (2009). Conceptualización de la praxis pedagógica del profesorado de bachillerato. Congreso: PEDAGOGÍA 2009. La Habana, Cuba. Memorías en CD propiedad autor.

Sánchez, N. E. A. (2018). El video como herramienta de apoyo en la educación superior. Tesis. Universidad Técnica de Ambato. Ecuador. Disponible en: https://repositorio.uta.edu.ec/items/4302ba70-6686-41d0-a3fb-cac172cd6fd9