Vol. 03, Issue 02 (2024): August-December

DOI: 10.53591/easi.v3i2.1866

ISSN-e: 2953-6634

Submitted: October 30, 2024

Revised: December 10, 2024

Accepted: December 12, 2024

Engineering and Applied Sciences

in Industry

University of Guayaquil. Ecuador

Frequency/Year: 2

Web:

revistas.ug.edu.ec/index.php/easi

Email:

easi-publication.industrial@ug.edu.ec

How to cite this article: Torres, J. et al. (2024). Comparison of the performance of the pyrolysis processes of PET, LDPE and PS, in a prototype batch process reactor. EASI: Engineering and Applied Sciences in Industry, 3(2), 47-56 https://doi.org/10.53591/easi.v3i2.1866

Articles in journal repositories are freely open in digital form. Authors can reproduce and distribute the work on any non-commercial site and grant the journal the right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Abstract. This document-template provides detailed instructions for preparing and submitting a paper Abstract. In this study, the critical factors of the pyrolysis process of plastics to obtain liquid hydrocarbons derived from petroleum were determined. The evaluation of these factors consisted of tests at specific temperatures of 350, 395 and 400°C using different types of plastics, such as polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polystyrene (PS) and low-density polyethylene (LDPE). The tests were carried out in a batch reactor with an average reaction time of 10 minutes. It was found that PS, processed at 395°C for 8 minutes, produced the highest number of liquid hydrocarbons, with an average yield of 91% by weight compared to the liquid products. In contrast, PET generated less than 30% of the product, while LDPE achieved a yield of 84%. The determining factors were the average temperature, the thermal insulation of the reactor and the selection of the type of plastic. Other factors, such as pressure and reaction rate, also proved to have a relevant impact on the process results.

Keywords: Pyrolysis of plastics, liquid hydrocarbons, plastic-to-fuels, plastics

Resumen. En este estudio se determinaron los factores críticos del proceso de pirólisis de plásticos para obtener hidrocarburos líquidos derivados del petróleo. La evaluación de estos factores consistió en la realización de pruebas a temperaturas específicas de 350, 395 y 400°C utilizando tipos de plásticos, como tereftalato de polietileno (PET), poliestireno (PS) y polietileno de baja densidad (LDPE). Las pruebas se realizaron mediante en un reactor discontinuo con un tiempo promedio de 10 minutos de reacción. Se encontró que el PS, procesado a 395°C durante 8 minutos, produjo la mayor cantidad de hidrocarburos líquidos, con un rendimiento promedio del 91% en peso comparado con los productos líquidos. En contraste, el PET generó menos del 30% de producto, mientras que el LDPE alcanzó un rendimiento del 84%. Los factores determinantes fueron la temperatura promedio, el aislamiento térmico del reactor y la selección del tipo de plástico. Otros factores, como la presión y la velocidad de reacción, también demostraron tener un impacto relevante en los resultados del proceso.

Palabras claves: Pirólisis de plásticos, hidrocarburos líquidos, combustibles plásticos, plásticos.

1. INTRODUCTION

Plastic pyrolysis is a process that breaks down polymers through heat, making it a useful option for managing waste and using it as secondary resources. In a world where environmental problems and the need to conserve natural resources are a priority, this method has gained relevance, especially because it can produce alternative fuels that benefit the transportation sector, one of the largest consumers of energy (Castro et al., 2019).

The constant growth of plastic waste worldwide, at an accelerated pace, represents a serious risk to the environment and human health due to the accumulation of waste (Cruz & Pulgarin, 2019). According to the UN (2022), “80% of marine litter comes from land-based sources, mainly from plastics used in food and beverage packaging, while the remaining 20% is originated from maritime activities. In Latin America and the Caribbean, 17,000 tons of plastic waste are generated daily.” Given this situation, initiatives such as the production of fuels from the pyrolysis of plastics have emerged. This process breaks down polymers in an environment with little or no oxygen, at temperatures typically ranging from 300 to 900 °C (Espinoza & Naranjo, 2014). Within this framework, the present study aims to explore the technical and operational feasibility of producing fuels derived from plastics by pyrolysis, considering key factors such as energy consumption, efficiency, quality of the products obtained and the associated environmental impact.

The efficient development of pyrolysis faces several challenges, such as the variety of plastic raw materials, the required temperature and time conditions, reactor design, by-product management and energy consumption of the system (Erdogan et al., 2020). The lack of complete knowledge on these aspects limits both the improvement of the process and its large-scale application (Borrelle et al., 2020). One of the main products of this method is pyrolytic oil, also known as pyrolyzed plastic oil (López et al., 2011). This oil has industrial and commercial potential, but its production brings up environmental problems, such as the emission of gases and volatile organic compounds that can damage air and soil quality (Jung et al., 2010). Direct burning of unrefined oil can release hazardous pollutants into the environment. Therefore, although pyrolysis has great potential, its environmental impact must be carefully managed (Magaña & Suárez, 2006). In addition, reducing plastic production and improving waste management are essential to mitigate the environmental problems related to these materials (Klug, 2012). High energy consumption is one of the biggest obstacles in the production of pyrolytic oil. As the search continues to reduce dependence on fossil fuels and promote more sustainable practices, pyrolysis is emerging as an interesting alternative (Ding et al., 2019). However, this process requires more energy than traditional fossil fuel production methods (Jahirul et al., 2022). Consumer plastics, especially single-use plastics, are very common, but their current production and use are unsustainable (Elordi et al., 2012). In 2019, global plastics production reached 368 million metric tons, and this figure is projected to double in the next 20 years. Most of these plastics are designed for single use and have limited recycling capacity. According to Espinoza & Naranjo (2014), this has led to an unprecedented accumulation of plastic waste and widespread environmental pollution. In fact, only 9% of global plastic waste has ever been recycled, 12% has been incinerated, and the remaining 79% remains accumulated in natural ecosystems (Walker & Fequet, 2023).

Borrelle et al. (2020) estimated that, in 2016, between 19 and 23 million tons of plastic waste reached aquatic ecosystems, and this figure is expected to increase to 53 million tons annually by 2030. In this context, energy recovery from solid waste, through liquid fuels, has gained global interest as a solution to environmental problems and the need to ensure energy security (Miandad et al., 2016). Although plastics are valued for their durability and resistance, characteristics that allow the production of long-lasting goods, they also generate serious environmental challenges. For this reason, it is crucial to promote recycling and reuse within a framework that complies with international environmental commitments (Castro et al., 2024).

1.1. Basis of the pyrolysis process

The pyrolysis process is based on the thermal decomposition of materials in the absence of oxygen. This method constitutes the initial stage in techniques such as combustion and gasification and is generally followed by partial or complete oxidation of the products obtained in the primary phase (Park et al., 2020). Pyrolysis takes place in three main stages: 1) the loading and supply of the raw material, 2) the conversion of organic compounds, and 3) the obtaining and subsequent separation of the final products, which include coke, bio-oil and gas. According to Subhashini & Mondal (2023), there are some key aspects of the process:

· Absence or low amount of oxygen: Pyrolysis is carried out in an environment with little or no oxygen. This lack prevents the complete combustion of the materials, favoring instead thermal decomposition.

· Temperature: The pyrolysis process requires heating the materials to high temperatures, generally between 0 and 500°C, depending on the materials and the objectives of the process.

· Gas emissions: During pyrolysis, gases such as methane, hydrogen, carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide are generated and released as gaseous products. These gases can be captured and used as energy sources or as raw materials for chemical products.

· Formation of liquids and tar: The process also produces liquids, which can include pyrolytic oil, tar, and other liquid byproducts. These liquids can serve as biofuels, feedstock for chemicals, or lubricants.

· Generation of carbonaceous solid waste: In some cases, pyrolysis produces carbonaceous solid waste, such as carbon coke or carbon black, which can be used in the manufacture of activated carbon and other applications.

1.2. Critical factors in the pyrolysis reactor prototype

These elements have diverse impacts at each stage of the process, affecting both the quantity and quality of the resulting product.

Type of plastic

The nature of plastic plays an essential role in determining the type and structure of hydrocarbons generated during pyrolysis. Pyrolysis of polyethylene terephthalate (PET), a material containing oxygen in its chemical composition, generates significant amounts of gases, among which carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide predominate. In addition, during processing, PET tends to produce acids that, according to various studies, can cause corrosion and weaken the structures used in the process (Abbas-Abadi et al., 2013).

Operating temperature

Due to their composition, plastics require a specific temperature to achieve the breakdown of their molecules and allow the conversion of the material (Sharuddin et al., 2016). In the case of polystyrene, research and tests have identified that its optimal temperature to achieve molecular decomposition and maximum conversion is 395 °C. This is considered a relatively low temperature, although close to the upper limit of this category (Park, Kim, Kwon, & Jeong, 2020).

Reactor type

Research by Wong et al. (2015) and Rajendran et al. (2020) highlights that the selection of the reactor type is a key factor in the pyrolysis process. This element can significantly influence aspects such as residence time, heating rate and temperature, which in turn directly impacts the quality of the final product.

In the experiments carried out, it was decided to use a batch reactor due to its simple design and ease of construction. This reactor operates as a closed system, where, once the raw material is loaded and the process begins, it is not possible to add or remove materials until the cycle has concluded.

Heating rate

The heating rate in a reactor refers to the speed with which the particles go from room temperature to the necessary one for their rupture and decomposition. According to Aguilar C. (2019), there are two main types of heating rates in the pyrolysis process: slow and fast.

Slow pyrolysis is characterized by a long retention time and a low heating rate, which increases the probability of generating waste (Muley et al., 2015). On the other hand, fast pyrolysis involves a rapid increase in temperature and short retention periods, which favors the production of liquid products while reducing the yield of solids and gases. In the experiments carried out, the fast pyrolysis process was carried out (Williams, 2007).

2. METHODOLOGY

This study is based on an experimental approach, as its main objective is to explore the technical and operational feasibility of producing fuels derived from plastics through the pyrolysis process. To do so, the key factors affecting this method were analyzed, such as energy consumption, process efficiency, quality of the products obtained and the associated environmental impact.

2.1. Prototype of the plastic pyrolysis reactor

For the process, 220g of plastic were recycled to perform the pyrolysis. Before using it, it was cleaned to remove impurities, ensuring that it only contained polystyrene. Then, the polystyrene was crushed to facilitate pyrolysis and allow its transition from solid to gas.

Description of the materials

In the construction of the prototype of the reactor for the pyrolysis of plastic, various materials were used, each meticulously chosen for its properties and technical characteristics. Vessel 1/Reactor, Vessel 2/Diesel Condenser, and Vessel 4/Gasoline Condenser: A cylinder designed for refrigerant storage was used, made of carbon steel or aluminum alloys, materials known for their high strength and durability. The cylinder specifications establish the maximum safe pressure levels that it can withstand. Vessels 1 and 4 were loaded with R-410A refrigerant, weighing 13,600 kg, while vessel 2 used R-22. Both are high-pressure refrigerants, and this cylinder was specifically designed to handle them. Its structure provides the strength necessary to withstand the high pressures involved during the process.

Vessel 3 with Copper Tubing: Copper was used to make some of the tubing and coils, as it is an excellent thermal conductor that improves heat exchange. Copper helps to optimize the efficiency of the cooling system.

Square Steel Tubes: These materials were essential for the construction of the prototype structure. They were selected due to their greater weight, high toughness, superior corrosion resistance, and ability to withstand extreme temperatures compared to aluminum. Additionally, they were chosen for their ease of welding and excellent machinability.

Supply Hose: These hoses were used to transfer the generated gas from the first vessel or reactor to the second vessel, as well as at the outlet of the fourth vessel. They are designed to withstand demanding conditions, including resistance to oxidation and corrosion. They have a maximum intermittent service temperature of up to 110 °C, a peak working pressure of 20 bar (295 PSI), and a minimum flow rate of 14 liters per minute at a pressure of 0.4 bar. In addition, they have rotating connections made of nickel-plated brass and/or acetal resin.

Copper Torch: To raise the temperature of the reactor, a copper torch connected to a gas cylinder was used, allowing control of the gas output and monitoring of the reactor temperature. This torch can reach temperatures of up to 1300°C when used correctly, being ideal for welding, baking and heating.

Prototype construction

The prototype design includes a reservoir specially designed to withstand temperatures ranging from 0 to 500 °C (Rajendran et al., 2020). The thermal resistance capacity of this component is essential, since it must receive and control the temperature increase necessary to transform the plastic, initially in a solid state, to its gaseous phase. This process is carried out in an environment without the presence of oxygen.

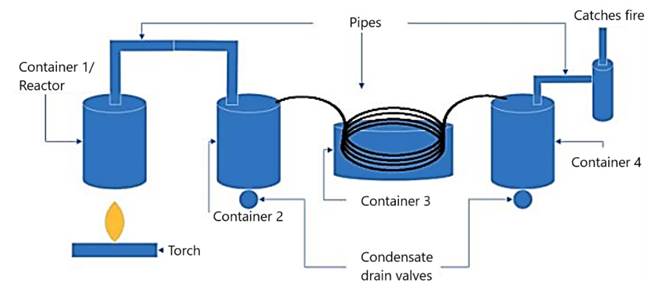

Figure 1. Prototype diagram. Source: Own elaboration (2024)

The manufacture of the reservoir used in the pyrolysis process, which operates in a temperature range between 0 and 500 °C, requires special attention in the selection of materials and design to ensure both its thermal resistance and durability.

At the initial stage of the project, an exhaustive resistance test was carried out on the material to confirm that it could withstand such temperatures. Once its suitability was confirmed, a circle with a radius of 164 mm was drawn to define the base of the lid (Figure 1). The prefabricated circle was then welded together, thus forming the support platform. Using a grinder, a precise cut was made in the cylinder to create the necessary hole, finally improving the surface with polishing using the same tool.

Figure 2. Plastic pyrolysis reactor prototype vessels. Source: Own elaboration (2024).

In the next stage, as shown in Figure 2, the lid was manufactured with a thickness of 3.5 millimeters, ensuring the robustness necessary for the design. Subsequently, the joints that allow the hoses to be screwed on were welded, guaranteeing the continuity of the process. To achieve a hermetic seal, a copper ring and a plastic ring were manufactured that function as seals for the lid. Finally, these components were secured using six screws with washers, allowing the successful completion of the construction of the container. In addition, half-inch holes were made with nipples to connect the first heating tank, along with nozzles designed for the exit of gases and their subsequent cooling.

The prototype's cooling system, also illustrated in Figure 2, includes a water container used to condense the gases and transform them from a gaseous state to a liquid before entering the last container. This system was designed using spirals previously manufactured from a copper pipe. The spirals, installed along two meters of pipe, facilitate the passage of gas and allow efficient cooling during the process.

Figure 3. Prototype for plastic pyrolysis. Source: Own elaboration (2024).

To complete the prototype, various connections were made through holes to allow the entry of the liquid, i.e. the fuel, through a nozzle between the tanks. To release gases, a second hole was placed in the second reservoir tank, avoiding pressure build-up and ensuring process safety. As can be seen in Figure 3, the entire system was mounted on a metal structure for user convenience, unifying the reactor and the containers. The prototype corresponds to an experimental system for the conversion and supply of liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) to produce PTF (Plastic-to-Fuels).

Process development

The process begins with the first container, where the temperature is increased to an average of 450 °C. This allows the plastic to go from solid to gaseous state, and the gas generated is directed to the following containers for processing. The temperature increase is achieved by means of a modified burner with a cyclone, which intensifies the heat, regulates the gas flow and ensures that the required temperature is reached.

In the second container, the gases enter through a pipe and condense inside, giving rise to the production of Diesel. This container is 3 mm thick and is equipped with a bronze key to extract the condensed pyrolytic liquid. The gas enters through the top through a half-inch nipple and is directed towards a copper spiral installed in the next container.

The third container contains a prefabricated copper spiral, located inside a 2 mm thick plastic container filled with water. This design allows the gas to be cooled efficiently, drastically reducing its temperature and facilitating its transformation into a liquid state before passing to the last container, where the gasoline-type fuel is obtained.

The last container, cylindrical in shape and 2.5 mm thick, includes a bronze key that allows the condensed pyrolytic liquid to be extracted. This liquid arrives through a copper pipe that passes through filters designed to refine and obtain gasoline-type fuel. As a safety measure, a system has been implemented that prevents an external flame from entering through the pipes and reaching the tanks that store the pyrolytic liquids, minimizing the risk of accidents. This system also facilitates the verification of the gas released during the burning of plastic.

Finally, to carry out the plastic pyrolysis tests, the steps described below were followed.

Material preparation: The material to be pyrolysed is selected and prepared, in this case, plastic waste.

Loading into the reactor: The material is introduced into a batch reactor, where the process will be carried out.

Sealing of the reactor: The reactor is closed to prevent the entry of oxygen, since pyrolysis is carried out in the absence of this gas.

Heating: The reactor is gradually heated to high temperatures, generally between 300°C and 500°C, depending on the type of material and the desired products.

Thermal decomposition: At these high temperatures, the organic material thermally decomposes in the absence of oxygen, producing gases, liquids and solid carbon.

Product Recovery: Products generated during pyrolysis are collected and, if necessary, subjected to additional processes to separate and purify specific components, such as distillation in the case of liquids.

Cooling: Pyrolytic products, such as gases and liquids, are cooled for further processing or storage.

Solid Waste (Ash): In some cases, solid waste is obtained in the form of ash or carbon. This waste must be removed from the system before further testing.

Product Applications: Pyrolytic products, such as gas and oil, can have various applications, such as power generation, chemical production, or materials manufacturing.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Based on previous research, three types of raw materials were selected to be tested with the prototype plastic pyrolysis plant: polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polystyrene (PS) and low-density polyethylene (LDPE). These materials were collected and subjected to a thorough cleaning process to remove any impurities. They were then crushed to facilitate their handling during the procedure.

Once the raw material was prepared, three tests were carried out with each material to evaluate its performance in the pyrolysis process and determine which was most suitable. In the first test, PET was subjected to pyrolysis at an average temperature of 400 °C, with a temperature increase of 40 °C per minute and a residence time of 11 minutes. During the test, considerable gas emissions were observed shortly after the start, which continued until the end of the process. At the end, the liquid product was collected, but PET showed poor performance in this technique. In addition, accumulated residues were detected both in the prototype pipes and inside the reactor, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Material clogged in the pipes, Residue from the PET process. Source: Own elaboration (2024).

In the next test, LDPE was pyrolyzed at an average temperature of 350 °C, with a temperature increase of 40 °C per minute and a residence time of 10 minutes. During the process, low gas emissions and waste generation were observed inside the reactor, although no waste was found in the pipes. The yield of the liquid obtained was higher than that achieved with PET, and the final product presented different shades compared to the liquids obtained from PET and PS.

Finally, in the last test, PS was pyrolyzed at an average temperature of 400 °C, maintaining a heating rate of 40 °C per minute and a residence time of 8 minutes. Under these conditions, PS was the material that was processed most quickly. In addition, it generated the highest liquid yield compared to the other materials analyzed. During this test, no residues were detected in either the reactor or the pipes, and the resulting liquid showed a color similar to that of the product obtained from PET.

Figure 5. Liquid yield of PS, LPDE and PET respectively. Source: Own elaboration (2024).

According to the tests carried out, and as can be seen in Figure 5, polystyrene (PS) is the material that provides the highest liquid yield in the plastic pyrolysis process. In addition, this material is easier to process compared to the other materials evaluated.

In this sense, the prototype allows us to conclude that PS is the most suitable raw material for the process designed in this study. Although it is possible to improve the yields of other types of materials by adjusting certain aspects of the design, for the purposes of this work it has been decided to use polystyrene. It should be noted that this material is flammable, but with subsequent treatment it can be transformed into a product suitable for combustion in engines.

3.1. Energy balance analysis

An initial reading of 28.51 kg and a final reading of 28.42 kg were recorded, reflecting a consumption of 0.09 kg of liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) as input energy. To calculate this energy, the change in weight was multiplied by the calorific value of LPG, obtaining a total of 1084.68 Kcal.

As for the output energy, it was determined from the amount of product generated, which was 150 g (0.150 kg), with a calorific value of 7917.74 Kcal/kg, based on the studies of Subhashini & Mondal (2023) and Ndiaye et al. (2023) on the pyrolysis of PS. This resulted in an output energy of 1187.661 Kcal. The difference between the energy used and the energy generated, corresponding to the energy dispersed in the environment, as seen in Table 1.

Table 1. Energy Balance in PS Pyrolysis Using LPG

|

Input energy |

|

Initial reading: 28,51 Kg. |

|

final reading: 28,42 Kg. |

|

Delta: 0,09 Kg GLP |

|

0,09Kg GLPx12.052 Kcal/Kg power=1084,68Kcal |

|

Output energy |

|

150g of product = 0.150Kg/producto |

|

0,15Kgx7917,74Kcal/Kg=1187,66Kcal |

|

Therefore: |

|

Energy input – Energy output = Energy dispersed in the environment / Energy loss 1084Kcal–1187,66Kcal=103,66Kcal |

During the pyrolysis process, an energy loss was identified, which is consistent with the second law of thermodynamics, which states that a portion of the energy will always be dissipated as heat. This loss is influenced by factors such as pressure, temperature, and the type of plastic used in the reactor (Rahman et al., 2023).

In the case of the prototype, the energy loss was related to thermal inefficiencies, attributable to inadequate heat transfer due to poor insulation of the reactor or thermal leaks in its walls. These limitations in heat transfer contribute to the formation of unwanted byproducts, reducing the efficiency of the process and generating significant energy losses.

Therefore, energy balance analysis is essential to assess the efficiency and performance of the system. The difference recorded between the incoming and outgoing energy, which shows a dispersion of 103.66 Kcal into the environment, underlines the importance of optimizing the process to minimize these losses. Understanding these dynamics is key to making informed operational decisions and presents the opportunity to implement improvements that promote more efficient and sustainable management of energy resources.

CONCLUSIONS

After carrying out and analyzing three plastic pyrolysis experiments using a prototype made of materials such as polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polystyrene (PS) and low-density polyethylene (LDPE), key factors affecting the process results were identified. These materials were subjected to high temperatures, which caused a chemical transformation in their molecules. During the process, the thermoplastic chains were broken, passing from a solid to a gaseous state and subsequently condensing into a pyrolytic liquid. Among the factors that directly influence the quality and quantity of the fuel produced are the type of plastic, the reactor design, the operating temperature, the pressure, the heating rate and thermal losses.

According to the results obtained, PS demonstrated greater fluidity in the liquid state after pyrolysis, which minimizes the risk of obstructions in the system's pipes. This feature contributes significantly to a more efficient operation and a more continuous production cycle. With an initial amount of 220 g of PS, it was observed that this material generates a higher liquid yield compared to the other plastics analyzed.

In addition to its high yield, PS presents advantages related to occupational safety. During its pyrolysis, the amount of gas generated is lower compared to other plastics, which significantly reduces the risks to workers' health. This aspect is crucial to assess the sustainability and viability of the pyrolysis process as a method to convert plastics into fuels. On the other hand, PET, although widely used, showed significant limitations in terms of operational efficiency and safety. With an initial amount of 440 g of PET, the volume of liquid produced was considerably lower, thus reducing the efficiency in fuel production.

LDPE, although viable for conversion into fuels, failed to surpass the liquid yield of PS. In addition, the LDPE pyrolysis process requires special attention to the optimal molecular breaking point, since exceeding this temperature for a prolonged time can affect the quality of the final product and even generate unwanted by-products.

Based on these findings, it is concluded that polystyrene is the most suitable plastic for pyrolysis in fuel production. Its advantages, including high liquid yield, lower risk of system blockages, and low gas generation, position it as the most efficient and safe option. A detailed analysis of these factors is essential to move towards the implementation of pyrolysis as a sustainable method of plastic waste management and fuel production.

However, considering that the pyrolytic liquid obtained presents high levels of impurities, it is recommended that future studies include the application of the catalysis process to eliminate these impurities and residues. This will allow its suitability for internal combustion engines to be evaluated by analyzing calorific and emission parameters (Krishna, 2020).

Acknowledgements

We, Torres Jorge, Vinces Milton, Castro Pedro and Arias Jaime, express our sincere gratitude to the EASI Journal of the University for the opportunity to publish our work. We deeply value the support provided during the editorial process and the commitment of its team to the promotion of academic knowledge.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest within this research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

REFERENCES

Abbas-Abadi, M. S., Haghighi, M. N., & Yeganeh, H. (2013). Evaluation of pyrolysis product of virgin high-density polyethylene degradation using different process parameters in a stirred reactor. Fuel Processing Technology, 109, 90-95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuproc.2012.10.018

Aguilar Carlos (2019). Repositorio institucional: Universidad de los Andes, Colombia. Obtenido de https://repositorio.uniandes.edu.co/server/api/core/bitstreams/e25211a1-f669-499d-b1ee-c385dae9d6c5/content

Borrelle, S. B., Ringma, J., & Rochman, C. M. (2020). Predicted growth in plastic waste exceeds efforts to mitigate plastic pollution. Science, 369(6510), 1515-1518. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aba3656

Castro-Verdezoto, P-, Vidoza J., Galo, W. (2019). Analysis and projection of energy consumption in Ecuador: Energy efficiency policies in the transportation sector. Energy Policy, 134, 110948. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2019.110948

Castro, P., Da Cunha, M., García, A., Quintero, W. (2024). Energy policy implications of Ecuador’s NDC. Journal of Infrastructure, Policy and Development 2024, 8(13), 7542. https://doi.org/10.24294/jipd7542

Cruz, J. F., & Pulgarin, A. C. (2019, diciembre 15). Impacto del reciclaje en la biodiversidad. ANZOO. http://anzoo.org/publicaciones/index.php/anzoo/issue/view/11/RCZ%20Vol%20 5%20%2310

Ding, K., Liu, S., Huang, Y., Liu, S., Zhou, N., Peng, P., & Ruan, R. (2019). Catalytic microwave-assisted pyrolysis of plastic waste over NiO and HY for gasoline-range hydrocarbons production. Energy Conversion and Management, 196, 130-137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2019.06.076

Elordi, G., Olazar, M., Castaño, P., Artetxe, M., & Bilbao, J. (2012). Polyethylene cracking on a spent FCC catalyst in a conical spouted bed. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, 51(40), 12816-12824. https://doi.org/10.1021/ie3018274

Espinoza, J. Naranjo, T. (2014). Diseño de una planta de reciclaje de plásticos en Cuenca. Universidad Politécnica Salesiana. https://dspace.ups.edu.ec/bitstream/123456789/7014/1/UPS-CT003680.pdf

Erdogan, S., & Sinan, S. (2020). Recycling of waste plastics into pyrolytic fuels and their use in IC engines. IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.90639

Jahirul, M., Faisal, F., Rasul, M., Schaller, D., Khan, M., & Dexter, R. (2022). Automobile fuels (diesel and petrol) from plastic pyrolysis oil—Production and characterisation. Energy Reports, 8, 1571-1581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2022.10.018

Jung, S.-H., Cho, M.-H., Kang, B.-S., & Kim, J.-S. (2010). Pyrolysis of a fraction of waste polypropylene and polyethylene for the recovery of BTX aromatics using a fluidized bed reactor. Fuel Processing Technology, 91(3), 277–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuproc.2009.10.009

Klug, M. (2012). Pirólisis, un proceso para derretir la biomasa. Professional Engineering Publishers. https://revistas.pucp.edu.pe/index.php/quimica/article/view/5547

Krishna Moorthy Rajendran, V. C. (2020). Review of catalyst materials in achieving the liquid hydrocarbon fuels from municipal mixed plastic waste (MMPW). Science of the Total Environment, 733, 139101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139101

López, A., Marco, I., Caballero, B., Laresgoiti, M., & Adrados, A. (2011). Dechlorination of fuels in pyrolysis of PVC containing plastic wastes. Fuel Processing Technology, 92(2), 253–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuproc.2010.10.011

Magaña, R. C., & Suárez, C. T. (2006, enero). Análisis del impacto ambiental de los plásticos en México. http://ri.uaemex.mx/bitstream/handle/20.500.11799/104205/secme16867_6.pdf?sequence=6&isAllowed=y

Miandad, R., Barakat, M., Aburiazaiza, A. S., Rehan, M., & Nizami, A. S. (2016). Plastic waste management: A review of pyrolysis technologies. Process Safety and Environmental Protection, 102, 822–838. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2016.06.022

Muley, P. D., Henkel, C., Abdollahi, K. K., & Boldor, D. (2015). Pyrolysis and catalytic upgrading of pinewood sawdust using an induction heating reactor. Energy & Fuels, 29(12), 8056–8065. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.5b01878

Ndiaye, N., Derkyi, N., & Amankwah, E. (2023). Pyrolysis of plastic waste into diesel engine-grade oil. Scientific African, 21, e01547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sciaf.2023.e01547

ONU. (2022). Noticias ONU: Plásticos y medio ambiente. Obtenido de https://news.un.org/es/story/2022/06/1509892

Park, C., Kim, S., Kwon, Y., & Jeong, C. (2020). Pyrolysis of polyethylene terephthalate over carbon-supported Pd catalyst. Catalysts, 10(5), 496. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal10050496

Rahman, M. H., Bhoi, P. R., & Menezes, P. L. (2023). Pyrolysis of waste plastics into fuels and chemicals: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 180, 133135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2023.133135

Rajendran, K. M., Chintala, V., Sharma, A., Pal, S., Pandey, J. K., & Ghodke, P. (2020). Review of catalyst materials in achieving the liquid hydrocarbon fuels from municipal mixed plastic waste (MMPW). Materials Today: Communications, 22, 100708. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtcomm.2020.100708

Sharuddin, S. D., Abnisa, F., Daud, W. M., & Aroua, M. K. (2016). A review on pyrolysis of plastic wastes. Energy Conversion and Management, 115, 308–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2016.02.037

Subhashini, S., & Mondal, T. (2023). Experimental investigation on slow thermal pyrolysis of real-world plastic wastes in a fixed bed reactor to obtain aromatic rich fuel grade liquid oil. Journal of Environmental Management, 343, 118184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.118184

Walker, T. R., & Fequet, L. (2023). Current trends of unsustainable plastic production and micro(nano)plastic pollution. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 163, 117037. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2023.117037

Williams, P. T., & Slaney, E. (2007). Analysis of products from the pyrolysis and liquefaction of single plastics and waste plastic mixtures. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 51(4), 754–769. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2006.12.002

Wong, S., Ngadi, N., Abdullah, T., & Inuwa, I. (2015). Current state and future prospects of plastic waste as a source of fuel: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 50, 1167–1180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2015.04.063