Tigua Villaprado Yoilera, Cadena Barrera Joaob, Castro Verdezoto Pedroa, Ortega Pacheco Daniela

aFaculty of Industrial Engineering, Universidad de Guayaquil. Guayaquil 090112, Ecuador.

bBioCarbon, Guayaquil, Ecuador.

Corresponding author: tigua1d@gmail.com

Vol. 04, Issue 02 (2025): October

ISSN-e 2953-6634

ISSN Print: 3073-1526

Submitted: August 26, 2025

Revised: September 10, 2025

Accepted: September 10, 2025

Tigua, Y. et al. (2025). Energy forecast of Ecuador’s Tertiary Sector to 2040 Using the LEAP Model. (n.d.). EASI: Engineering and Applied Sciences in Industry, 4(2), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.53591/easi.v4i2.2596

This study forecasts energy consumption in Ecuador’s tertiary sector through 2040 using a prospective energy model developed with LEAP software. It relies on official data and variables such as employment figures and household consumption. Three scenarios are analyzed: Business as Usual (BAU), High (HIGH), and Low (LOW) consumption. Results show an 87% increase in energy use between 2020 and 2040, rising from 5 million to 10 million barrels of oil equivalent (BOE). Under the BAU scenario, consumption is projected at 10 million BOE; 6 million in the LOW scenario; and 13 million in the HIGH scenario. Out of 11 activities analyzed, 84% of energy use is concentrated in three key areas: Information and Communication, Commerce, and Accommodation and Food Services. The sector also displays a strong reliance on electricity, which represents 76% of its total energy consumption. Transportation services were excluded from the analysis, as they are considered a separate sector due to their high energy demand. The findings highlight the urgency of implementing sustainable strategies to manage energy use, especially in high-consumption activities. This information provides a valuable foundation for decision-makers and stakeholders in designing energy policies focused on efficiency and reducing environmental impacts in Ecuador’s tertiary sector.

Keywords: Energy consumption; Tertiary sector; Energy forecasting; LEAP model.

The Ecuadorian economy has undergone a significant structural transformation in recent decades, shifting from a model primarily based on agriculture and the extraction of natural resources to one where the tertiary sector plays a dominant role. This sector, which includes commerce, financial services, education, health, and communications, currently represents 51.85% of the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and accounts for 53.02% of national employment (Salinas, 2022). This growing prominence of the tertiary sector has been accompanied by a notable increase in energy demand, raising important concerns regarding sustainability and energy efficiency (Castro-Verdezoto et al., 2024). Although the sector is generally less energy-intensive than industry or transport, its rapid expansion has contributed to a rise in greenhouse gas emissions. In 2023, electricity covered approximately 80% of the energy demand within Ecuador’s tertiary sector, while diesel accounted for around 12% (IIGE, 2024). The reliance on non-renewable energy sources—particularly petroleum derivatives—and the volatility of their international prices further underscore the urgency of diversifying Ecuador’s energy matrix and improving energy use within the tertiary sector.

A comparative perspective also reveals structural contrasts in energy consumption. In Europe, the service sector accounts for approximately 14% of total energy use (Tsemekidi et al., 2023), whereas in Ecuador, this figure is significantly lower, at just 6.1% (IIGE, 2024). Notably, in both regions, the tertiary sector ranks fourth in overall energy consumption. Similar trends are observed in neighboring countries with comparable economic characteristics: in Peru, the sector represents 5% of total energy consumption (Mamani, 2022), and in Colombia, 5.6%. Yet, despite its relatively low energy consumption, the tertiary sector contributes substantially to the economies of these countries—accounting for 62% of Peru’s GDP (2023) and 60% of Colombia’s GDP (2024a). Ecuador follows a similar pattern, with the sector contributing over 50% to national GDP (Salinas, 2022).

However, research focused specifically on energy consumption in Ecuador’s tertiary sector remains limited. This gap in the literature hinders the formulation of targeted policies that promote energy efficiency and environmental sustainability. The recent national energy crisis—triggered by drought-induced reductions in hydroelectric generation and the interruption of electricity imports from Colombia—has further exposed the fragility of Ecuador’s undiversified energy supply and highlighted the need for more robust, long-term planning(2024b).

Given these challenges and opportunities, this study aims to forecast energy consumption in Ecuador’s tertiary sector—excluding transport, due to its distinct energy profile—through the year 2040. Using the Long-range Energy Alternatives Planning (LEAP) model, the analysis will incorporate official data and key variables such as employment figures and household consumption (Benito et al., 2024). The findings will serve as a foundation for policymakers and stakeholders to design energy strategies that enhance efficiency and reduce environmental impacts in one of Ecuador’s most economically significant sectors.

For the study of energy planning, the LEAP (Long-range Energy Alternatives Planning System) model will be used. This is a versatile tool that allows for the analysis of energy systems under different methodological approaches, including end-use accounting and scenario simulation (LEAP, 2024). LEAP will be complemented with a bottom-up model, which focuses on a detailed analysis of energy demand, enabling the evaluation of interactions between specific sectors and technologies (Pérez-Gelves et al., 2024). This approach is fundamental for identifying improvements in energy efficiency and projecting future consumption under various scenarios (Castro et al., 2018). The combination of both models will provide a comprehensive view, both at the macroeconomic level and in terms of specific technologies and sectors, which is essential for designing sustainable and effective energy policies (Castro Verdezoto et al., 2019).

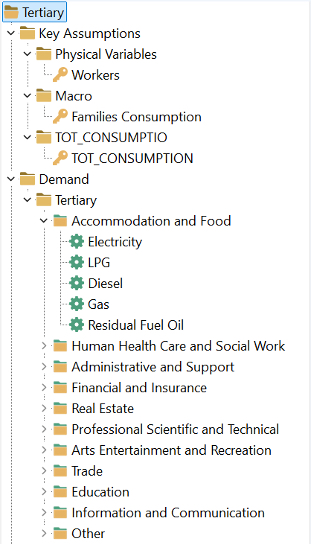

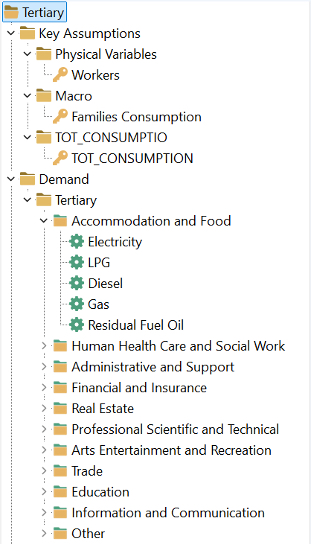

The same classification used in the 2020 National Energy Balance was adopted, which categorizes the tertiary sector based on the types of fuels consumed: electricity, liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), diesel, gasoline, and fuel oil (Figure 1).

To project the energy consumption of the tertiary sector, an analysis of the main influential variables in scientific research was conducted. The key variables identified include Household Consumption and the Number of Employees. According to studies such as those by (Wei et al., 2007; Zhou & Gu, 2020), household consumption is crucial for estimating energy intensity in economic sectors, particularly in China, where this consumption represents almost a quarter of the total. On the other hand, studies on the Nigerian economy by (Ali et al., 2021) and the International Energy Agency (IEA, 2015) highlight that the number of employees in a sector is a significant predictor of energy consumption.

Subsequently, a correlation analysis was conducted between Energy Consumption and Household Consumption, revealing a very strong correlation (0.97) between these two variables. This suggests that as Household Consumption increases, so does Energy Consumption. The same pattern is observed between Energy Consumption and the Number of Employees, with a correlation of 0.87, indicating that as the Number of Employees grows, Energy Consumption also increases. Finally, the correlation between Household Consumption and the Number of Employees (0.94) is positive and very strong, almost as high as that observed between Energy Consumption and Household Consumption. This demonstrates a close relationship between these variables, where an increase in household consumption may be linked to a rise in economic activity that drives job creation, and vice versa (see Table 1).

Table 1. Equipment used.

| Variable | Energy Consumption |

|---|---|

| Household Consumption | 0.97 |

| Employees | 0.87 |

The multiple correlation analysis showed a coefficient of 0.989, an R² of 0.977, an adjusted R² of 0.972, and a standard error of 93.34. These results indicate a very strong relationship between the variables, excellent predictive capacity, and a reasonable error, confirming that the model is accurate and reliable for projecting energy consumption in the tertiary sector.

The following equation was used to project energy consumption:

| $$EC=\left(CF\ast\alpha\right)+\left(NE\ast\beta\right)+\gamma$$ | (1) |

where:

To convert the different units of energy consumption obtained from ENESEM, the Energy Statistics Manual of (Manual Estadística Energética 2017, 2017). Was used the Barrel of Oil Equivalent (BOE) was employed, a unit used by the IIGE, the entity responsible for preparing the National Energy Balance in Ecuador. Additionally, to estimate the energy intensity of each activity in the tertiary sector (Figure 2), the relationship between BOE and the sector's energy consumption was used.

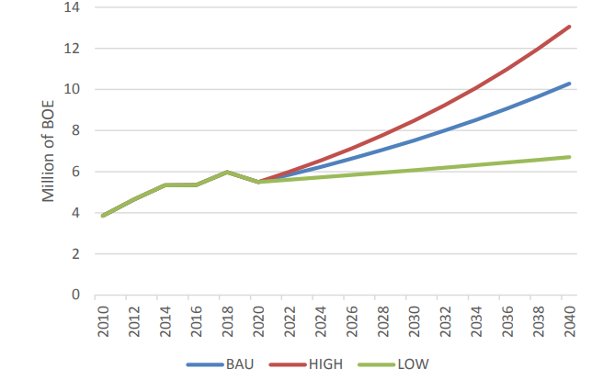

Three scenarios were developed: BAU (Business as Usual), HIGH, and LOW. For the BAU scenario, an annual growth rate of 3.35% in the number of workers was projected until 2040, while for the HIGH scenario, a growth rate of 4.66% was estimated, and for the LOW scenario, a growth rate of 0.17%. Regarding household consumption, an annual growth rate of 3.18% was projected for the BAU scenario, 4.42% for the HIGH scenario, and 1% for the LOW scenario. These percentages were based on the historical behavior of variables in the Ecuadorian economy (Matriz Insumo Producto, 2020), enabling the evaluation of different trends and their impact on future projections. They were also validated by the findings of (Bravo et al., 2016) who conducted an energy foresight study for the period 2012–2040.

In the BAU scenario, the tertiary sector's energy consumption stands at 10,282 kBOE. By contrast, in the HIGH scenario, this figure rises to 13,059 kBOE. On the other hand, the LOW scenario forecasts a reduction in energy consumption, estimating a decrease to 6,709 kBOE. This results in a 27% increase in the HIGH scenario compared to the BAU scenario, while the LOW scenario projects a 35% reduction relative to the BAU scenario. The HIGH scenario emphasizes the need for proactive energy planning to avoid overdependence on non-renewable resources, while the LOW scenario reveals potential vulnerabilities of economic contraction on energy use.

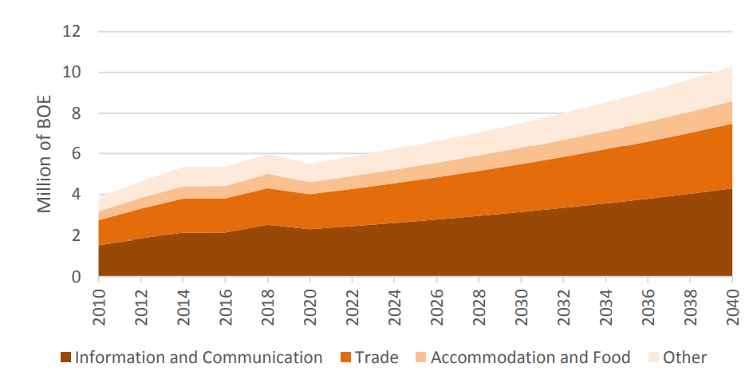

Figure 4 reveals a highly concentrated pattern of energy consumption in the Ecuadorian tertiary sector by 2040. The Information and Communication sector alone is projected to account for 42% of total energy use, reflecting the country’s increasing dependence on digital technologies, cloud computing, and data center facilities that require a continuous electricity supply for operation and cooling. This trend raises important concerns about the resilience of Ecuador’s electricity grid and the environmental impact of these energy-intensive digital systems. The Commerce sector follows with 31%, highlighting the sustained energy requirements for lighting, air conditioning, refrigeration, and electronic systems in retail environments. These needs will likely intensify with urban expansion and extended business hours. The Accommodation and Food Services sector, representing 11%, contributes through energy use in hospitality operations, including heating, cooling, food storage, and kitchen appliances. The remaining 16% is distributed among other service activities, which, although individually less demanding, together still constitute a significant portion of the sector's consumption. This distribution suggests that while energy efficiency efforts should prioritize the top three sectors, broader policies must also address the cumulative impact of the remaining service activities.

By 2040, the energy mix of Ecuador’s tertiary sector is projected to be heavily reliant on electricity (76%), followed by diesel (16%), LPG (7%), and other sources (1%) (Figure 5). While the dominance of electricity suggests progress toward cleaner energy, it simultaneously exposes the sector to significant risks. Ecuador’s dependence on hydroelectricity makes the system vulnerable to climate events like droughts, as demonstrated in recent crises. Without greater diversification through solar, wind, and energy storage, this reliance could jeopardize energy security and service continuity. Notably, the share of fossil fuels in the energy mix is relatively low. Diesel (16%) and LPG (7%) represent declining roles in the sector’s energy profile, signaling progress toward energy transition. The decreasing reliance on these fuels is encouraging, as it opens the door for further electrification in subsectors like hospitality, where LPG is still used for cooking and heating. Similarly, diesel often reserved for backup power can be gradually replaced by cleaner alternatives with adequate policy support.

Although the model provides robust projections, its accuracy depends on assumptions about future economic growth and stability. Using historical average growth rates may fail to capture sudden shocks, such as pandemics or political crises. Another limitation lies in the aggregation of diverse economic activities under broad categories, which could mask differences in energy efficiency practices across subsectors. Alternative approaches, such as hybrid top-down and bottom-up models incorporating behavioral variables, could offer more nuanced insights. From a policy perspective, the results support implementing energy efficiency standards, particularly in high-demand subsectors. Additionally, fiscal incentives for renewable energy adoption and mandatory energy audits for large tertiary-sector businesses could significantly reduce projected consumption in high-demand (HIGH) scenarios.

Ecuador should promote the adoption of non-conventional renewable energy sources, such as solar and wind power, leveraging its privileged geographical location. The country benefits from stable solar radiation levels year-round and consistent wind currents in regions like Loja, Esmeraldas, and the central highlands. To encourage private investment in this sector, the government could implement periodic renewable energy project auctions, tax exemptions, and state or mixed financing, following successful examples like Chile (En Chile, Codelco adjudica 1,5 TWh anuales de energía renovable para 2026-2040, 2025), which has transformed its energy matrix through competitive bidding. Furthermore, decentralizing power generation by mandating photovoltaic systems in tertiary-sector buildings, especially high consumption facilities like shopping malls, hotels, clinics, and universities should be prioritized. This approach has already been adopted in regions like California, where all new buildings must incorporate solar panels (2018).

Another key strategy is enhancing urban energy resilience through microgrids with energy storage in cities like Quito, Guayaquil, and Cuenca. These microgrids, powered by solar energy, backup batteries, and complementary sources such as biogas or small local hydropower plants, would ensure a continuous supply for critical sectors (healthcare, telecommunications, security, and commerce) even during grid failures. International experiences, such as those in India and Puerto Rico, demonstrate that microgrids are effective solutions for communities or strategic sectors vulnerable to natural disasters or centralized system failures (Sokol, 2023). Their adoption in Ecuador would not only improve system reliability but also advance the transition toward a more sustainable and decentralized energy system.

The analysis of Ecuador’s tertiary sector energy scenarios (BAU, HIGH, and LOW) underscores the need for policies that reconcile economic growth with sustainability. While the HIGH scenario projects a 27% rise in energy demand—driven by digitalization and AI—the LOW scenario’s 35% reduction, though environmentally favorable, is economically untenable due to its association with recession and poverty. This dichotomy highlights that decarbonization must be pursued without compromising development, particularly in high-demand subsectors like Information and Communication, Commerce, and Accommodation/Food Services. Given electricity’s dominance (76.06% of sectoral consumption), strategic priorities should include scaling renewable generation (especially solar and wind) and improving grid efficiency through modernization and incentives for energy-saving technologies. Crucially, the link between employment, household spending, and energy demand reveals that future policies must integrate socioeconomic variables into planning, such as through dynamic modeling or pilot programs for urban microgrids. To move beyond theoretical scenarios, Ecuador should implement targeted measures: mandatory energy audits, subsidies for efficient equipment, and workforce training to reduce energy intensity while sustaining growth. By focusing on these actionable steps, the country can transform its tertiary sector into a model of resilient, low-carbon development—aligning climate goals with energy security and equitable progress.

To deepen understanding of Ecuador's tertiary sector energy dynamics, future research should integrate dynamic modeling that incorporates behavioral and macroeconomic variables—such as analyzing how wage fluctuations influence service-sector energy consumption—while also implementing pilot programs to test microgrid resilience in urban hubs like Quito and Guayaquil. Additionally, developing sector-specific efficiency metrics will be critical to move beyond aggregate data, enabling tailored policies that address the unique realities of high-demand subsectors and ensuring adaptive, evidence-based energy strategies.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest within this research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ali, Z., Shaikh, F., Kumar, L., Hussain, S., & Memon, Z. A. (2021). Analysis of energy consumption and forecasting sectoral energy demand in Pakistan. International Journal of Energy Technology and Policy, 17(4), 366. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJETP.2021.118338

Andrew Khouri. (2018, mayo 9). California lista para exigir paneles solares en todas las casas nuevas. Los Angeles Times. https://n9.cl/fp5ux

Benito, A. O., Castro Verdezoto, P. L., Burlot, A., & Arena, A. P. (2024). Hybrid power system for distributed energy deploying biogas from municipal solid waste and photovoltaic solar energy in Mendoza, Argentina. E3S Web of Conferences, 532, 01001. https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202453201001

BCE. (2020). Matriz Insumo Producto [Dataset]. https://n9.cl/fvb0u

BCRP. (2023). PBI por sectores del Perú. https://n9.cl/estadisticasbcrpdatapbi

Bravo, G., Di Sbroiavacca, N., Dubrovsky, H., Lallana, F., Landaveri, R., Recalde, M., & Ruchansky, B. (2016). Estudio de Prospectiva Energética del Ecuador 2012-2040. https://n9.cl/ayhil

BRC. (2024). Banco central de Colombia Estadísticas económicas. https://n9.cl/gbbcw

Castro, P. L., Castro, M. P., & Cunha, M. P. (2018). Comparative analysis of energy indicators of the Andean Community Members Análisis comparativo de indicadores energéticos de Países miembros de la Comunidad Andina de Naciones.

Castro, P. L., Vidoza, J. A., & Gallo, W. L. R. (2019). Analysis and projection of energy consumption in Ecuador: Energy efficiency policies in the transportation sector. Energy Policy, 134, 110948. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2019.110948

Castro-Verdezoto, P. L., Da Cunha, M. P., García-Gutiérrez, Á., & Montaño, W. Q. (2024). Energy policy implications of Ecuador’s NDC. Journal of Infrastructure, Policy and Development, 8(13), 7542.

IEA. (2015). Indicadores de Eficiencia Energética: Bases Esenciales para el Establecimiento de Políticas. https://biblioteca.olade.org/opac-tmpl/Documentos/cg00333.pdf

IIGE. (2024). Balance Energético Nacional 2023. Instituto de Investigación Geológico y Energético. https://www.recursosyenergia.gob.ec/5900-2/

Ini, L. (2025, abril 24). En Chile, Codelco adjudica 1,5 TWh anuales de energía renovable para 2026-2040. pv magazine Latin America. https://n9.cl/jmmd3

LEAP. (2024). LEAP. https://leap.sei.org/default.asp?action=introduction

Mamani, R. M. (2022). Balance Nacional de Energía 2022.

OLADE. (2017). Manual Estadística Energética 2017. https://biblioteca.olade.org/opac-tmpl/Documentos/old0380.pdf

Pérez-Gelves, J. J., Castro-Verdezoto, P. L., Alvarado-Cantos, N. M., & César, T. A. (2024). Applying fuzzy logic and neural networks to forecasting in efficiency programs. In E3S Web of Conferences (Vol. 532, p. 01006). EDP Sciences

Salinas, M. E. (2022). Sector terciario y su aportación al PIB del Ecuador durante los diez últimos años [bachelorThesis]. https://repositorio.uta.edu.ec/handle/123456789/36672

Sokol, N. J. (2023). Chapter 19 - Community adaptation to microgrid alternative energy sources: The case of Puerto Rico. En M. Nadesan, M. J. Pasqualetti, & J. Keahey (Eds.), Energy Democracies for Sustainable Futures (pp. 173-179). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-822796-1.00019-X

Tsemekidi, S., Bertoldi, P., Economidou, M., Clementi, E. L., & Gonzalez-Torres, M. (2023). Determinants of energy consumption in the tertiary sector: Evidence at European level. Energy Reports, 9, 5125-5143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2023.03.122

Voz de América. (2024, abril 16). Ecuador inicia racionamientos de electricidad; Noboa destituye a ministra de Energía. Voz de América. https://www.vozdeamerica.com/a/ecuador-inicia-racionamientos-de-electricidad-de-hasta-cinco-horas-a-causa-de-la-sequia/7572051.html

Wei, Y.-M., Lan-Cui Liu, Ying Fan, & Gang Wu. (2007). The impact of lifestyle on energy use and CO2 emission: An empirical analysis of China’s residents. Energy Policy, 35(1), 247-257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2005.11.020

Zhou, X.-Y., & Gu, A.-L. (2020). Impacts of household living consumption on energy use and carbon emissions in China based on the input–output model. Advances in Climate Change Research, 11(2), 118-130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accre.2020.06.004